Petőfi for All Seasons

Political Changes in the Petőfi Cult between 1942 and 1956

design: BOGYÓ Virág

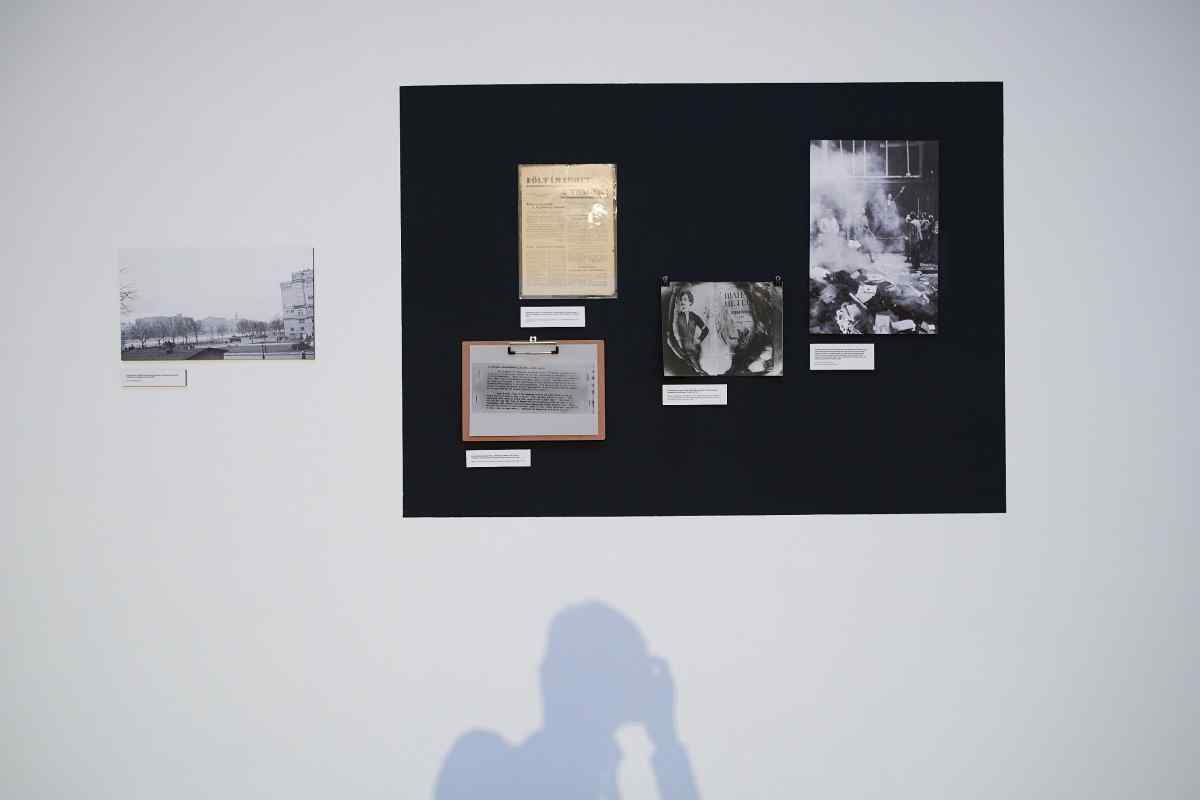

Budapest Poster Gallery

Fortepan

Hegyvidéki Helytörténeti Gyűjtemény, Budapest

Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum – Történeti Fényképtár / Hungarian National Museum, Historical Photo Department

MTVA Archívum – Nemzeti Fotótár / MTVA – National Photo Archive, Budapest

Nemzeti Filmintézet / National Film Institute, Budapest

Országos Széchényi Könyvtár / National Széchényi Library, Budapest

Historical myths and the evocation of historical heroes were—and still are—usually needed by political regimes that cannot justify their existence or their power by their own right, on the basis of popular consent and legitimacy, or of their own performance in promoting the common good. The period between 1942 and 1956 was the most turbulent period of an already turbulent 20th century in Hungarian history. Defeat in war, genocide, successive waves of political persecution, five successive regime changes, the fall of political regimes, the Arrow Cross coup, the communist coup, the revolution, and then, as the last event in this sequence, the counter-revolution and the restoration of the dictatorship.

Yet there is a common thread running through the period: each successive and opposing set of political actors needed Petőfi to lend credence to their political goals and ambitions for power. The war propaganda of the Horthy regime referred to him, as did the Arrow Cross movement which overthrew it. Petőfi’s banner was raised by various groups protesting against the war, the German occupation and the Arrow Cross coup. In the spring of 1948, the Communists timed the most important steps of their takeover, nationalization, party unification and the liquidation of political opposition, to the centenary of 1848, while putting the “holy trinity” of Petőfi, Kossuth and Táncsics on a pedestal. The Rákosi regime disguised itself as the fulfilment of Petőfi’s revolutionary dreams, but Petőfi also served as the symbol of social resistance to this Hungarian version of Stalinist dictatorship, and then of the 1956 revolution itself. Then the Kádár regime, which crushed the revolution with Soviet help, again found its historical archetype in Petőfi.

Petőfi for all seasons. The exhibition uses contemporary films, photographs and documents to show the political transformations of the figure of Petőfi, and the consecutive attempts to expropriate his memory in this narrow but all the more traumatic decade and a half.

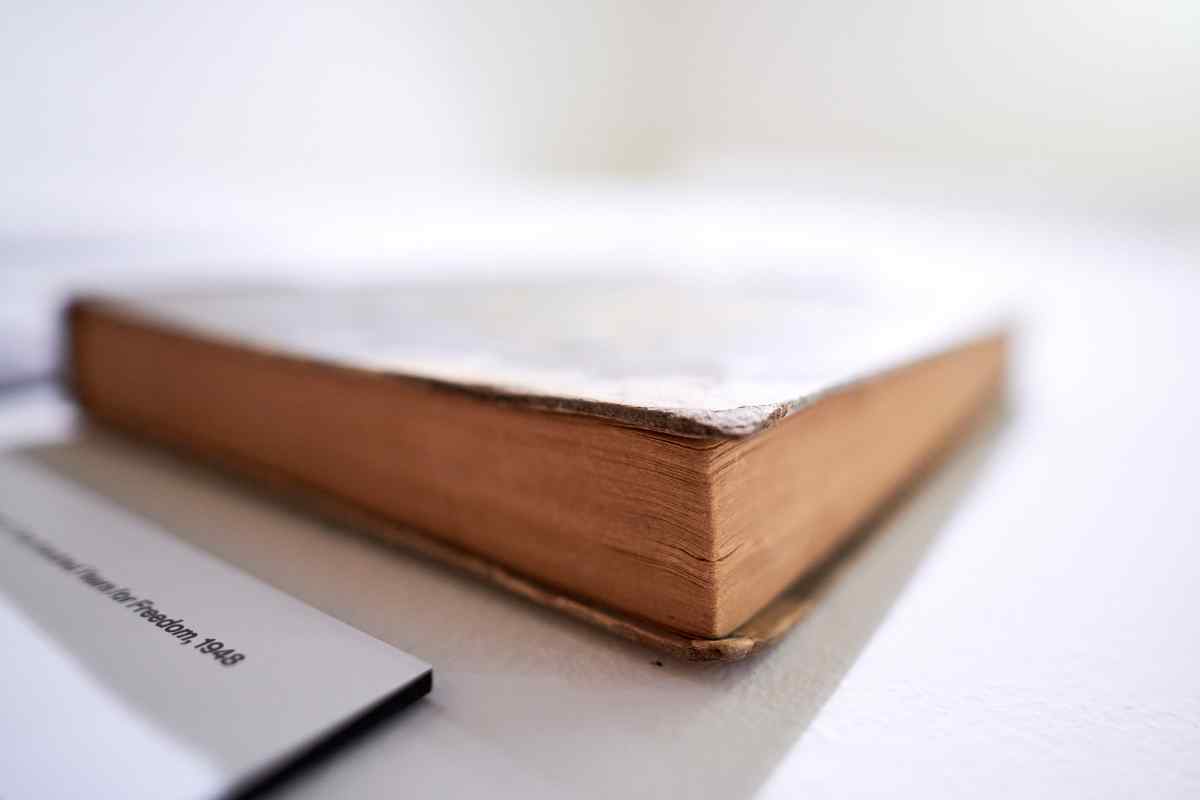

The exhibition is partly based on the Archivum’s 1998 show Fifty Years Ago It Was a Hundred Years Ago.