The Missing Staircase

Part of the “Traces of the Revolution” Program Series

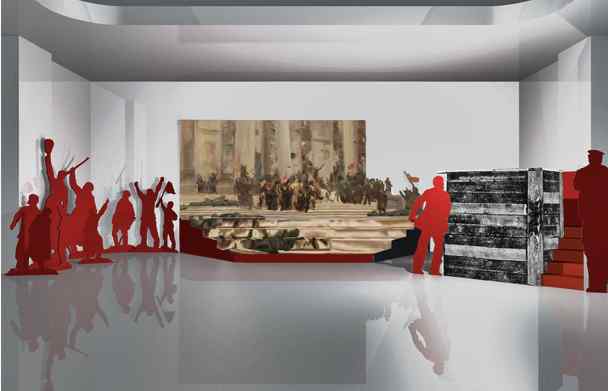

installáció, tervezte I installation by RAJK László (építész és designer / architect and designer)

graffiti l graffiti by SPITZMÜLLER József

grafika I graphic design SÁNDOR Dávid

Whatever we think about Communists and the revolution, it is hard to deny that the Bolsheviks changed the course of history on November 7, 1917 (according to the Gregorian calendar), when they besieged and occupied the Winter Palace. The Bolshevik revolution did not only define the history of the 20th and presumably subsequent centuries, but also our understanding of the past, including the French revolution and the 19th century. As Engels put it in his letter to a Russian revoliutsionerka in 1895: “Once 1789 arrives [in Russia], 1793 [the terror] is sure to come soon too.” Lenin and the Bolsheviks planned to re-enact, partly, the French revolution.

The influential revisionist historian of the French revolution François Furet thought that the seeds of Bolshevism were sown by the French revolution. In 1989 American historian Simon Schama wrote that everybody was reluctant to forcefully topple the Communist rule, and the regime could fall peacefully apart, because the adversaries of Communism faced the issue “Do not all revolutions which take the French revolution as their model become foul?; does not the revolutionary road lead straight from liberation to tyranny?”

In this part of the world, the officially recognized and remembered revolutions—the violent toppling of the regime—are presented to the celebrating public as elevating, glorious events which let the people experience popular sovereignty and the power to take their future into their own hands. No matter that October 23 is a foggy autumnal day; it is the celebration of youth, renewal, resurrection and purity, just as March 15 is.

Revolutions, naturally, always happened differently than they are remembered by posterity, with its ever-changing perspective. In Galina Alexandrovna Zubchenko’s painting “The Siege of the Winter Palace” of 2002, the revolutionaries storm the palace on the staircase leading up to the entrance of the building. Yet, there are no stairs at the Palace Square side of the building. However, a cursory glance at the picture, auctioned in Ireland in 2009, is enough to see that it is a copy of Petr Krivonogov’s 1948 painting “Red Army soldiers raising the Soviet flag over the Reichstag”. The many bodies on the steps are not heroically fallen revolutionaries but executed fascist German soldiers.

The victorious siege appears more heroic as a battle to climb a flight of stairs than merely to enter a ground floor door. And after all, according to Soviet historiography, the foundations of the victory over Fascism were laid by the Bolshevik revolution.

Today we know better: we know the costs of a revolution. The fate of revolutions is (almost? always) tragic downfall, treason, retaliation, death. As Engels, quoting Hegel, pointed out, the irony of history is that in the end a revolution is something totally different from what the leaders imagined for themselves at the outset. That is why all too often the attempt to win freedom results in autocracy, oppression, violence, or sheer stupidity in the end. The utopia of the Bolshevik revolution cost several tens of millions of lives.

Revolutions, however, are not fought by the smart but by those who are fed up; who do not consider the consequences but only want to end the present. Contrary to all our historical knowledge, there are moments in history when there seems to be no choice, or it is clear that we have only one choice.

In the framework of the “The Traces of the Revolution” program series that is part of the one-year program series “What's Left?”.