From Harvest to Harvest

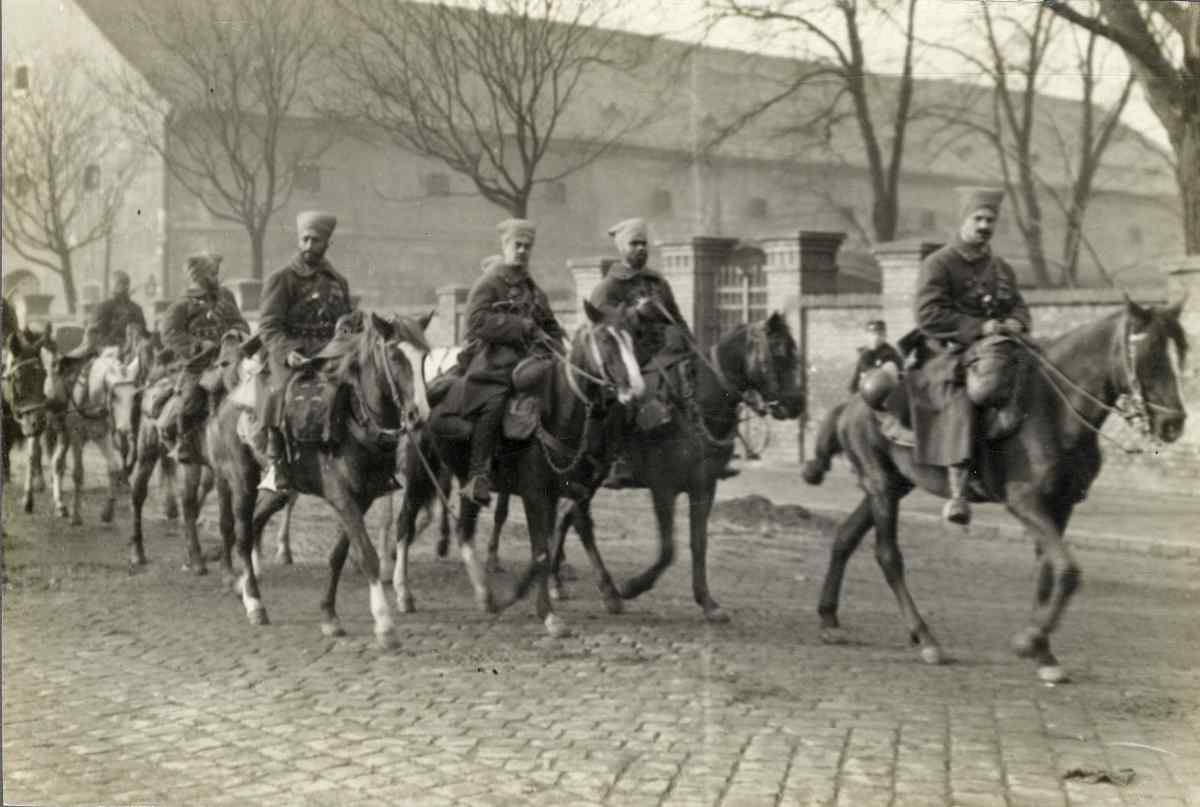

Hungarian Calvary, 1918–1919

kiállításdesign és grafika I exhibition and graphic design by BOGYÓ Virág

Hungarian Calvary – Hungarian Resurrection is the title Oszkár Jászi, the Hungarian civic radical politician, chose for his book on the history of the Aster Revolution and the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Jászi spent most of his life after 1919 as a political emigré; his book was published in Vienna in 1920. His conclusion was that for Hungarians, the Bolshevik attempt—which had “run amok,” as he put it—had for years to come discredited all democratic, liberal political ideas, movements and any hope of a freer and more just society in Hungary.

It appears that his prediction has, in fact, come true. After more than a century, democratic “resurrection” is yet to come. At the same time the official historical narrative of the Orbán regime, similarly to the views propagated by its cherished predecessor, the Horthy regime, has identified the scapegoat responsible for the collapse and dissolution of the Hungarian Kingdom (“Historical Hungary”) in the 1918 Aster Revolution and 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic. In their view, the two were essentially identical; the original sin was the Aster Revolution, which then paved the way for the Bolshevik takeover. Both aimed to destroy the old Hungarian Kingdom, eliminate the true historical traditions of the Hungarian nation, and displace the nation from its own country.

“Reinstalled by the Hungarian Parliament in commemoration of the murdered, maimed, devastated, and persecuted victims of the Communist scoundrels who came to power under the shadow of Soviet arms,” thus reads the inscription on the newly rebuilt Monument of National Martyrs. The monument was inaugurated on October 31, 2019, on the 101st anniversary of the assassination of István Tisza, who was the Premier of the Hungarian Kingdom throughout the First World War. In his inaugural speech, Speaker of the House László Kövér added: “Those one thousand or so people who held Hungary hostage under the disguise of mendacious slogans were driven by angry anti-Christianity, zealous internationalism, intense hate of the nation, a firm determination to destroy family life, and the greedy desire to despoil the people. . . . The descendants of the Lenin-boys are still facing us today and—for the time being by virtual means—have picked up where the Szamuelys and Csernys, the (communist criminals), left off a hundred years ago.” Kövér believes that Tisza was killed by the Communists (though the Communist Party did not yet exist in Hungary when the Premier was murdered) and by a false analogy he claims that nowadays once again it is just the virtual “Communists,” a handful of anti-national fanatics, who oppose Orbán’s rule.

Against the background of similar falsifications and attempts at demonization—faithfully exemplified by the above quotation—, this exhibition endeavors to show the events that occurred in Hungary in 1918–1919 in their real domestic and international context. In doing so, it hopes to shed light on those still unsettled traumas of the age, which could never become mere history in Hungarian collective remembrance.

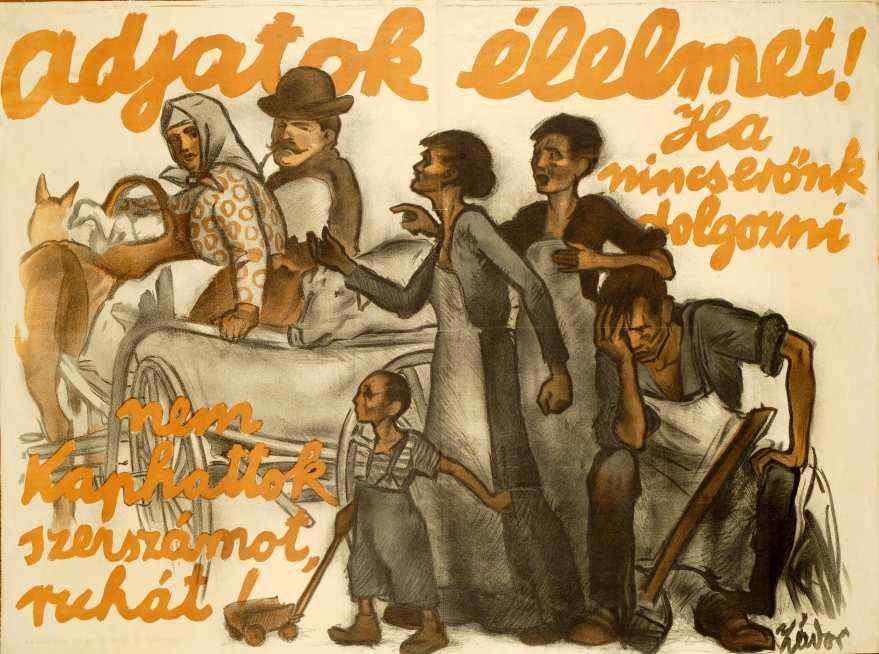

Our starting point is that by the Fall of 1918, it was not only the Hungarian state that collapsed: the whole of the previous political system came to a dead-end at the same time. Both the Aster Revolution and the Bolshevik takeover were reactions to the incomprehensible grievances of the lost war and to a wide range of social and political problems that the Hungarian political elite of the Dual Monarchy had been unable and unwilling to address—or nursed false illusions about their nature. The political passion and social tensions that the two revolutions brought to the surface, the initially high expectations and enthusiasm that mobilized wide sections of society, including a large part of the contemporary intelligentsia, were all fueled by the previous regime’s inability to face and resolve these problems. To mention but a few: despite dynamic modernization, the rigid and constrained political system remained untouched. Suffrage was the most limited in contemporary Europe. Both society and the prevailing political culture preserved their hierarchical, caste-like character. The claims of national minorities were ignored or suppressed, policies of forced assimilation prevailed. The unimaginable extent of urban and rural poverty remained unaddressed. Finally, the illusion of national sovereignty—which was in clear contradiction with the country’s actual dependence on Austria, which had actually dragged it into the war—rendered Hungary’s elite incapable of making appropriate preparations for the potential consequences of a lost war.

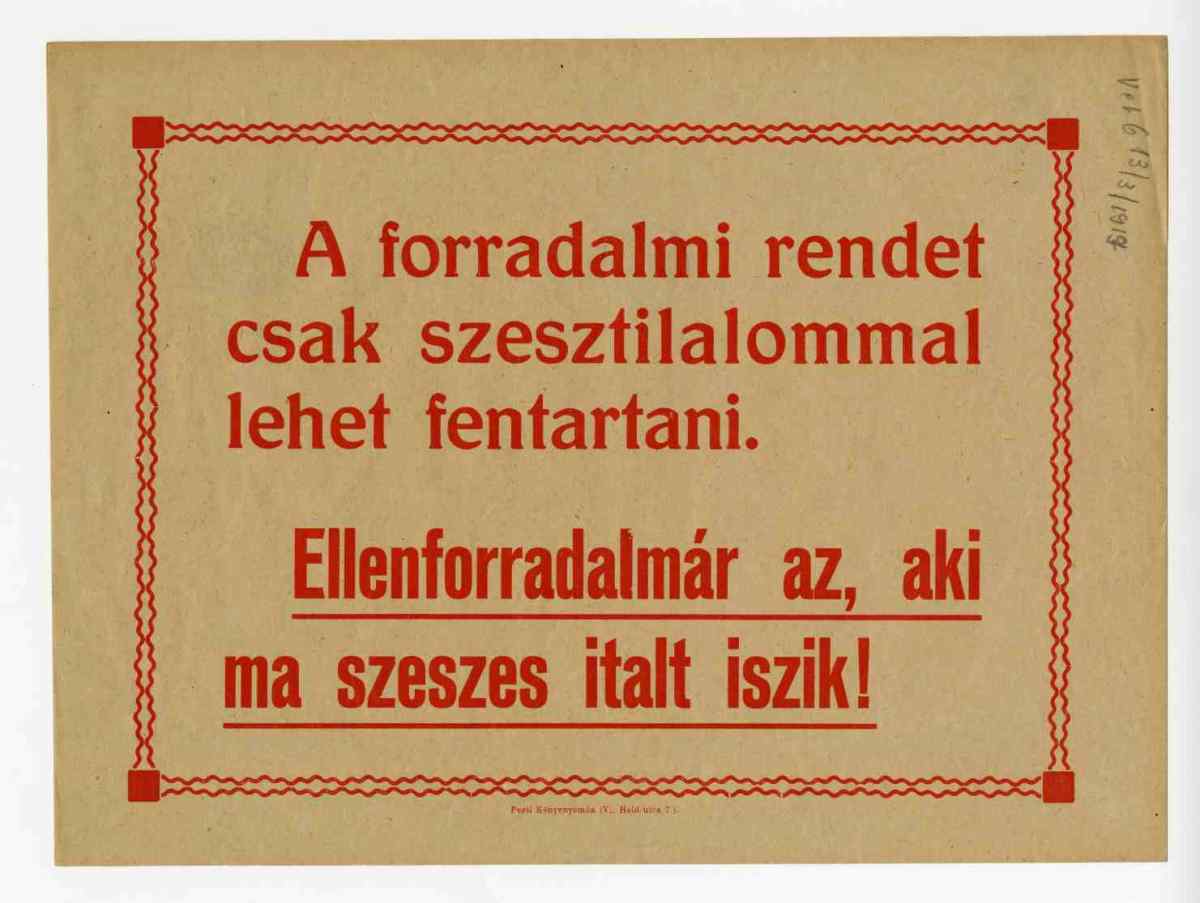

It was not Mihály Károlyi, the President of the Hungarian Republic in 1918, nor Béla Kun, the leader of the Communist Party, who were responsible for all of these pitfalls, miseries, and self-deceptions. March 21, 1919, the day of the Bolshevik coup, marked the start of the endgame to a series of irremediable processes and events. The country, forsaken by its king and ruling elite, fell into the hands of self-styled political amateurs who embraced daydreams of the proletarian world revolution, while, at the same time and for a short period, they represented the only hope of a way out for the people of a country which had been pushed to the edge of total breakdown and dissolution. They represented the last hope of restoring order and saving something from under the debris. It was not the fault of the people that the new rulers were unable to fulfill these expectations, and, in fact, were reluctant to even try.

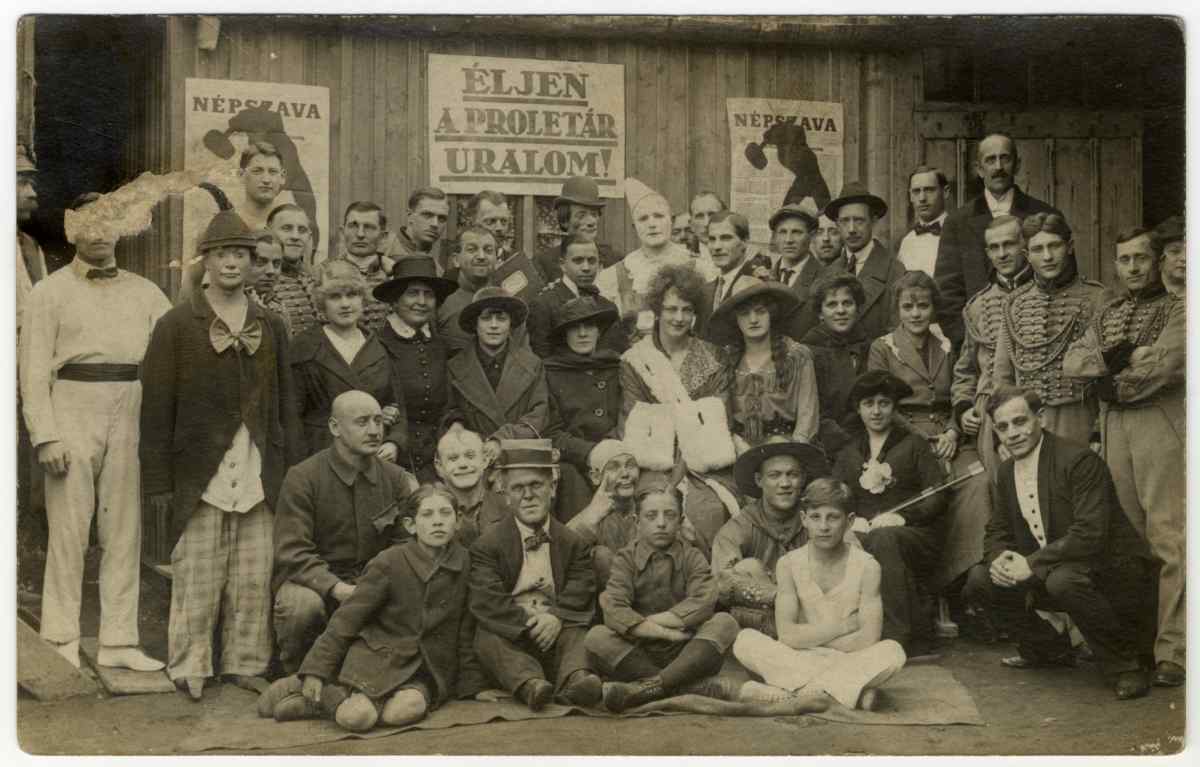

The drama of 1918–1919, the shocking twists and turns—the lost war, the dissolution of the Monarchy and the Hungarian Kingdom, the Aster Revolution, the rise and fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the counterrevolution, and Admiral Horthy’s rise to power—all took place within a year. From harvest to harvest.