Secession and Magnetism

The Effects of 1968 on Contemporary Hungarian Art

ALTORJAY Sándor, ALTORJAY Gábor; ATTALAY Gábor; BAK Imre; BALOGH István Vilmos; BERCZELLER Rezső; BIRKÁS Ákos; CSÁJI Attila; DUCKI Krzysztof; ef ZÁMBÓ István; ERDÉLY Miklós; FICZEK Ferenc; FREY Krisztián; GALÁNTAI György; GÁYOR Tibor; GELLÉR B. István; GULYÁS Gyula; GYÉMÁNT László; HALÁSZ Károly; HARASZTY István; HARIS László; HENCZE Tamás; KARÁTSON Gábor; KEMÉNY György; KESERŰ Ilona; KONDOR Béla; KONKOLY Gyula; LAKNER László; LOSSONCZY Tamás; MAUER Dóra; NÁDLER István; PAIZS László; PÁLFALUSI Attila; PAUER Gyula; PINCZEHELYI Sándor; SÁROS András Miklós; SISKOV Ludmil; SZENTJÓBY Tamás; TÓT Endre; TÓTH Gábor; TÜRK Péter; VESZELY Ferenc

The secession: 1966–1968–1972. The wars in Vietnam and in the Middle East; the cultural revolution in China, accompanied by the spread of Maoism and neo-Trotskyism; the events of 1968 in Paris and Prague, followed by the invasion of Czechoslovakia; the student movements and rebellions in North and Central America; the emergence and practical consequences of the notion of a post-industrialist, consumer society; the concept and reality of alienation; the elevation of structuralism to a religion; the effects of the hippie movement, rock music and drugs on culture; the spirit and practice of counter-culture and the underground; and all these in conjunction with the beginning, and the almost immediate failure, of the Hungarian economic reforms and the process of consolidation in Hungary: all these together posed an unprecedented challenge for the Hungarian artists too.

The exhibitions organized in Budapest from the mid-1960s onwards—although they still took place under illegal or semi-legal conditions—clearly demonstrated that progressive Hungarian art was present in the contemporary world. This is how Gyula Konkoly recalled the spirit of the time: “In early 1969 I made a giant paintbrush and a tiny one, followed by a gigantic telephone; then, during the summer, while doodling around in preparation for the second Armory show (that is to say, the IPARTERV exhibition of 1969, H.I.), I discovered art conceptuel. And so did Szentjóby. We moved with universal time and identical causes produced identical effects together. Nothing like that had happened in Budapest for a long, long time! (...) and my first work, made in homage to the vernissage commemorating October 23—four blocs of ice first treated with permanganate and then dressed in gauze, making sure that the ‘blood’ started to soak through the virgin snow-white fabric during the vernissage—were thrown into the furnace of IPARTERV's heating system, because people had thought they contained a live lamb... And then, in December, the great didactic exercise ‘to have five identical-looking people meet’ in Leninváros; followed by the joint exhibition with Imre Bak in the Fényes Adolf Hall, the helpless water, the viewer made visible, the great stocks with the memorials... at that time, we were light-years ahead of half of Europe. You had Tamás Szentjóby's cooling water, the portable trenches, and the new meter (...)! We were there in 1970 and, to give a firm answer to my joking riddle ‘Is it better to be a famous person in Pest or to be a waiter in Nice?’, I decided to emigrate. (...) Those were beautiful years, spent in euphoria: the great edifice of state culture had collapsed on its own: I don't mean the ideology, of course, only its flirtatious affair with fine art.”

The situation was so controversial, it was almost tragicomic. With his “super-exhibition” held in the Palace of Art, Victor Vasarely finally came home in 1969. Soon afterwards a huge exhibition was organized in the same venue to honor Henry Moore’s life work. Hungarian artists living abroad (many of whom played important roles in the international Avant-garde) had their retrospective exhibitions in Budapest, with the official commentators heaping lavish praise on them. At the same time, the severity of internal censorship never abated: sometimes even the police were called in, as the case of the closing of the chapel exhibitions of Balatonboglár, for example. The exhibitions held around the turn of the decade displayed works composed in the spirit of informel, hard-edge and kinetic art side by side, while the works of Hungarian artists representing the most recent developments, such as minimal art, concept art, arte povera, or hyper-realism, also made their first appearances.

Most of the works offered sensitive, frank and authentic answers to the problems that the artists on the international art scene were currently struggling with. But that weighed very little with the critics controlled by politics. In a manner that was sometimes insensitive, sometimes crudely ideological, these critics, who often proceeded by sifting through the heaps of philosophical rubble and invariably took the standpoint of ultimate rejection, tried to describe, and to eliminate, the new tendencies. They were not entirely unsuccessful, either: between 1970 and 1975, several Avant-garde artists emigrated to the West, while many of those who remained here decided to give up creative artwork altogether—some of them for good. At the same time, scores of artists who enjoyed state support began to apply, and thus to devalue, the stylistic marks and attitudes of the Avant-garde, with the result that these systematically vilified tendencies were diluted and made them more readily consumable: they could do it without “punishment”, because they had sold out their principles. By the mid-1970s, the Hungarian Avant-garde, after having been burdened with constant and infertile misunderstandings, was thrown into a state of confusion. The confusion was exacerbated by the effect of concept art, which was at the same time deliberating and disorientating, along with the Hungarian Avant-garde discovering itself, with all the pains and masochistic pleasures of such a self-discovery. And when you consider the drabness of the “surrounding settings”, the constant changing of art, with the arrogant hostility of concept art towards objects and its generosity in an incredibly small-minded world, you will see how tortuous the effects might have been.

With a great deal of over-simplification, one could identify the presence of three “movements” in the early 1970s. One of these tendencies had an expansive, sociological nature, which was sensitive to “fate” and reacted, directly or indirectly, to political events, by using the artistic arsenal of concept art and performance, while also showing strong affinities for movies and theater.

The other group, which operated on the border between literature and visual arts, ironically described itself as an apolitical movement. Its members interpreted their outsider attitude as a gesture of existential philosophy. According to their brief manifesto, “... THE UNDERGROUND ... is Non-official art. It is an art ‘movement’, which neither supports nor attacks the establishment; rather, it remains outside it. By attacking it, it would acknowledge its existence. If it was a real, organized movement, it would, again, play by the rules of the superficial world. It does not ban its followers from addressing political topics, because it can neither ban nor command; but whenever such a topic emerges, that is the private affair of the artist concerned. The coordinates of the underground are free-moving coordinates. What does the Hungarian underground want? It wants to be an art movement that defies identification and analysis; one that remains an outsider; and one that cannot be sized up or corrupted. A PRIVATE ART. Who does it speak to? It speaks to itself; its artists speak to each other; and it speaks to anyone who takes an accommodating interest in it. Although it does not expect recognition, when recognition comes, it is appreciated. What kind of a relationship do members of the underground have with each other? A friendly one.” (Béla Harp, “Halk magyar underground-kiáltvány/A soft-spoken manifesto by the Hungarian underground”, Szétfolyóirat, Vol. 1., February 1973)

By its nature, the third group was similarly apolitical, although its frequent clashes with the official position on art, along with its aesthetic and pedagogical principles and decidedly activist character, invested it with a political dimension. Its members elevated the democratization of art to an artistic program through the use of the Bauhaus principles.

Although contemporary art represented at relatively well-documented events (the IPARTERV exhibitions of 1968 and 1969, the exhibitions of Szürenon, the R-klub of 1972 and finally Balatonboglár) can more or less be reconstructed from numerous anthologies and monographs on individual oeuvres, it is not even remotely clear what kind of a direct influence the events of 1968 exerted on Hungarian art as a whole.

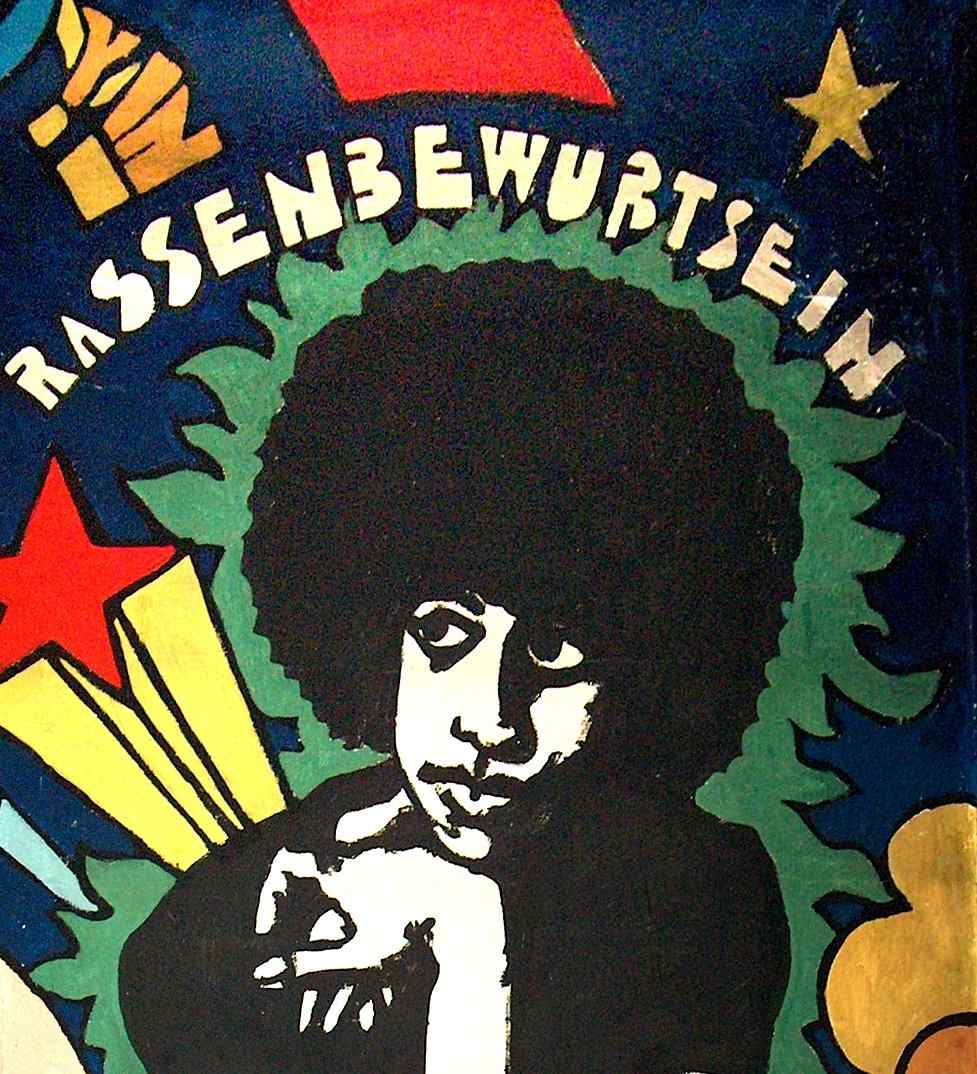

The aim of this exhibition, in addition to offering the reflections of well-known Avant-garde tendencies, is to demonstrate the deeper and longer-lasting, perhaps even magical, impact of those events; to show that the period left a mark even on those artists who, according to the consensus of previous public and professional opinion, were untouched by the influences of contemporary intellectual and political movements; it is also the aim of the exhibition to show that, regardless of the fact that they remained outside the art groups typical of the period, many artists were able to create autonomous values in the same area; that is, in being affected by the impressions of 1968. In other words, the organizers of the exhibition want to look beyond the familiar categorizations of new and neo-Avant-garde in order to be able to illustrate the impact of the period's universal values on contemporary Hungarian art. And this can explain why many of the compositions can evoke years far away in time from 1968, because the influence of 1968 lived on for a long time - at least in the area of fine arts.

István Hajdu