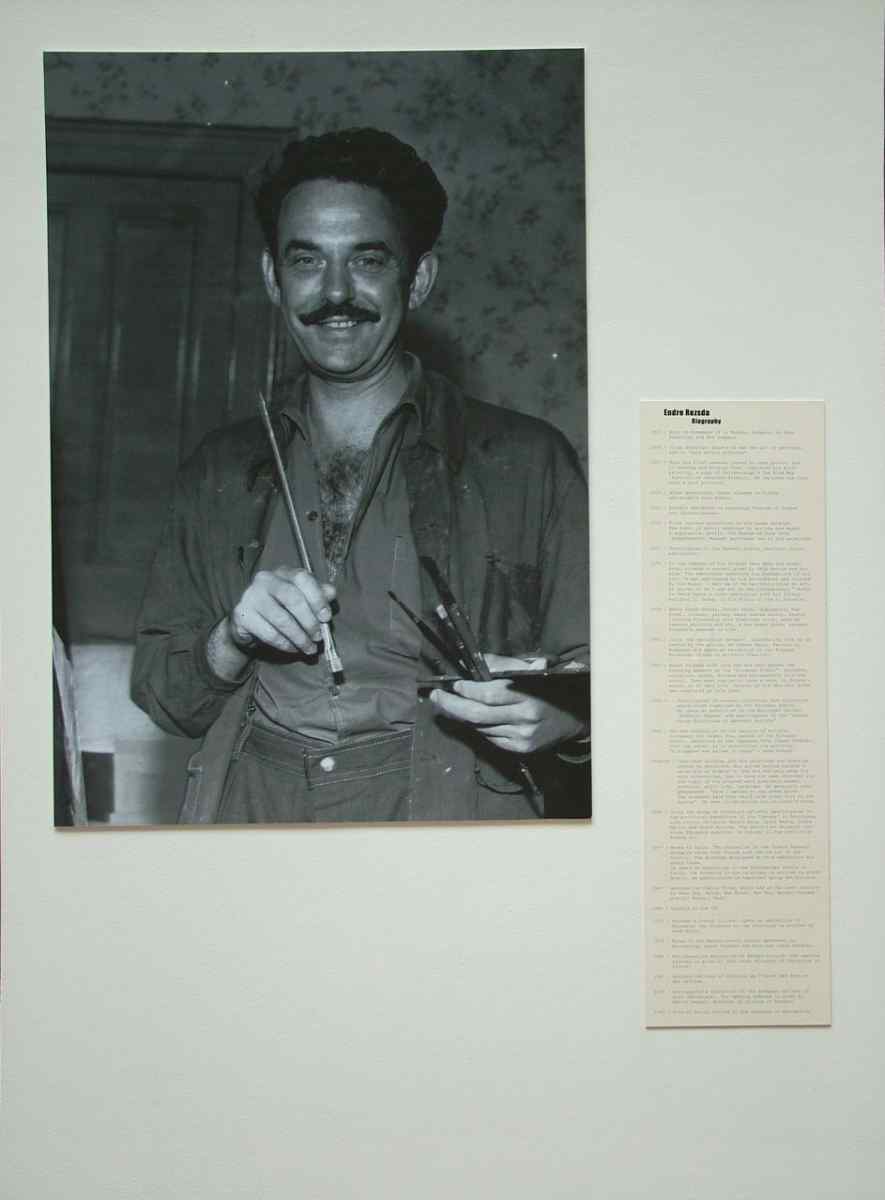

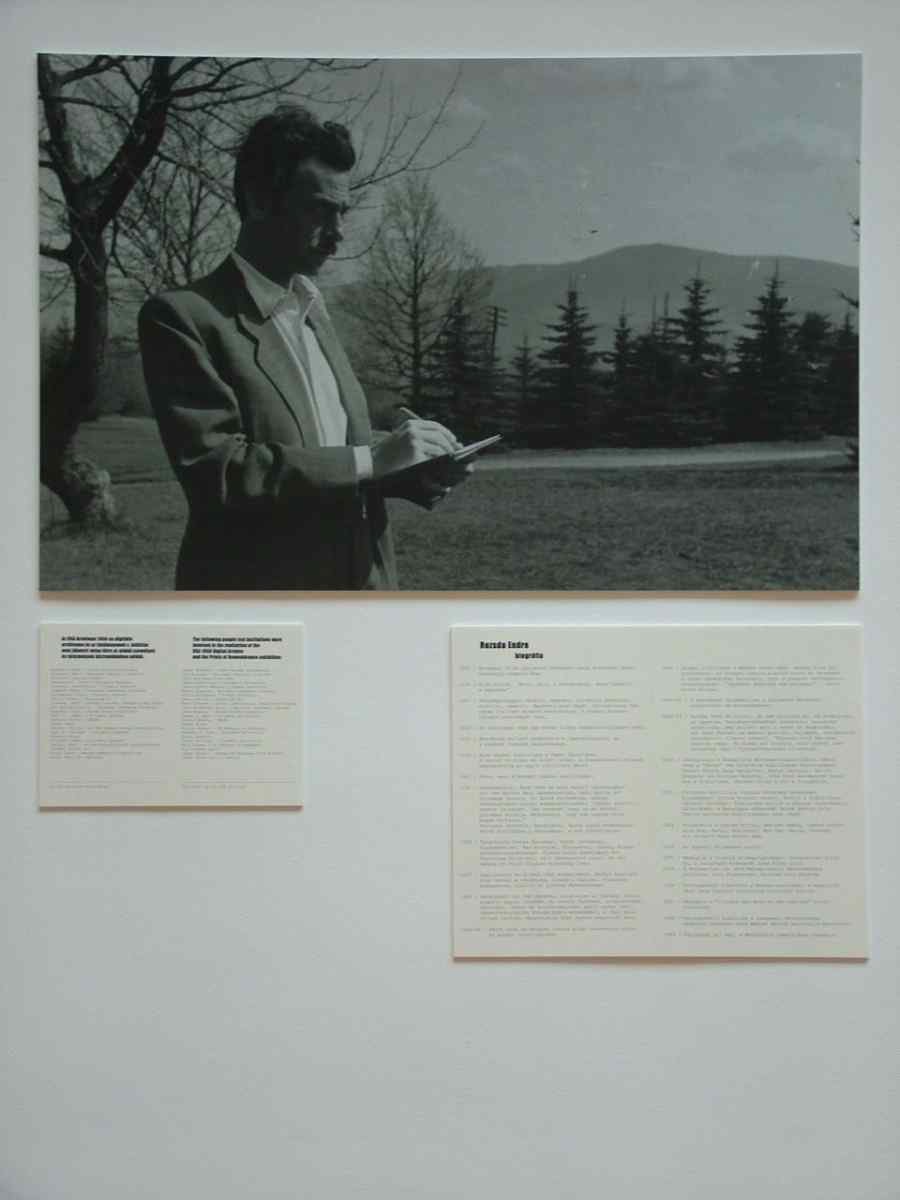

Prints of Recollections

Drawings by Endre Rozsda, Interviews with 1956 Refugees

ROZSDA Endre

design: TAMÁSI Miklós

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian revolution, OSA Archives has copied and digitized the Hungarian refugee interviews conducted in 1957 and 1958 within the framework of the Columbia Research Project Hungary (CURPH). After the suppression of the revolution almost two hundred thousand Hungarian citizens opted to escape and find a new home abroad. They were not only the primary eye-witnesses to the revolution itself but also to life under Communism. The Soviet bloc during and after the Stalin era was a hermetically closed orbit. The self-image projected by these regimes seemed both enigmatic and threatening to outside observers. Therefore, the Hungarian refugees, like other Eastern European refugees who managed to flee to the West throughout the 1950s taking with them their experiences and knowledge, were a vital source of information on the everyday reality under Communist rule. What made the Hungarians particularly important was not only their arrival in one great wave but also the fact that they had witnessed something inconceivable at the time: the people had brought down in a single blow a regime that had been deemed unshakable. Western observers hoped that the eye-witness accounts of the Hungarians would reveal the concealed mechanism of the Stalinist state and the mystery of its collapse.

CURPH was not the only program that targeted this issue. Nevertheless, it was the best organized and most elaborate project. More than 600 interviews were conducted by specially trained, native Hungarian field-workers in European refuge camps and in the United States. Most of the interviews lasted two or three days, and the final English transcripts averaged 70 pages each. The interviews were based on a detailed questionnaire, interview guidelines that had been carefully worked out by sociologists and public opinion experts. In those times these disciplines were much less developed than today. However, some of the early classics in these fields gathered their first professional experience within the framework of this project. Prominent scholars Henry Roberts and Paul Zinner, the forerunners of Kremlinology, worked on setting up the project and the evaluation of the results alongside Siegfried Kracauer and Paul Lazarsfeld, philosophers and sociologists from the “Frankfurt school”. The researchers did not limit their inquiry to the events of the revolution. Hundreds of questions aimed at uncovering the details of everyday life, the living standard, working conditions, social changes, cultural developments, changes in public mentality and morality, ideological indoctrination, religious matters and the survival of traditional values. All in all, the survey targeted the elusive totality of the human condition under totalitarian rule.

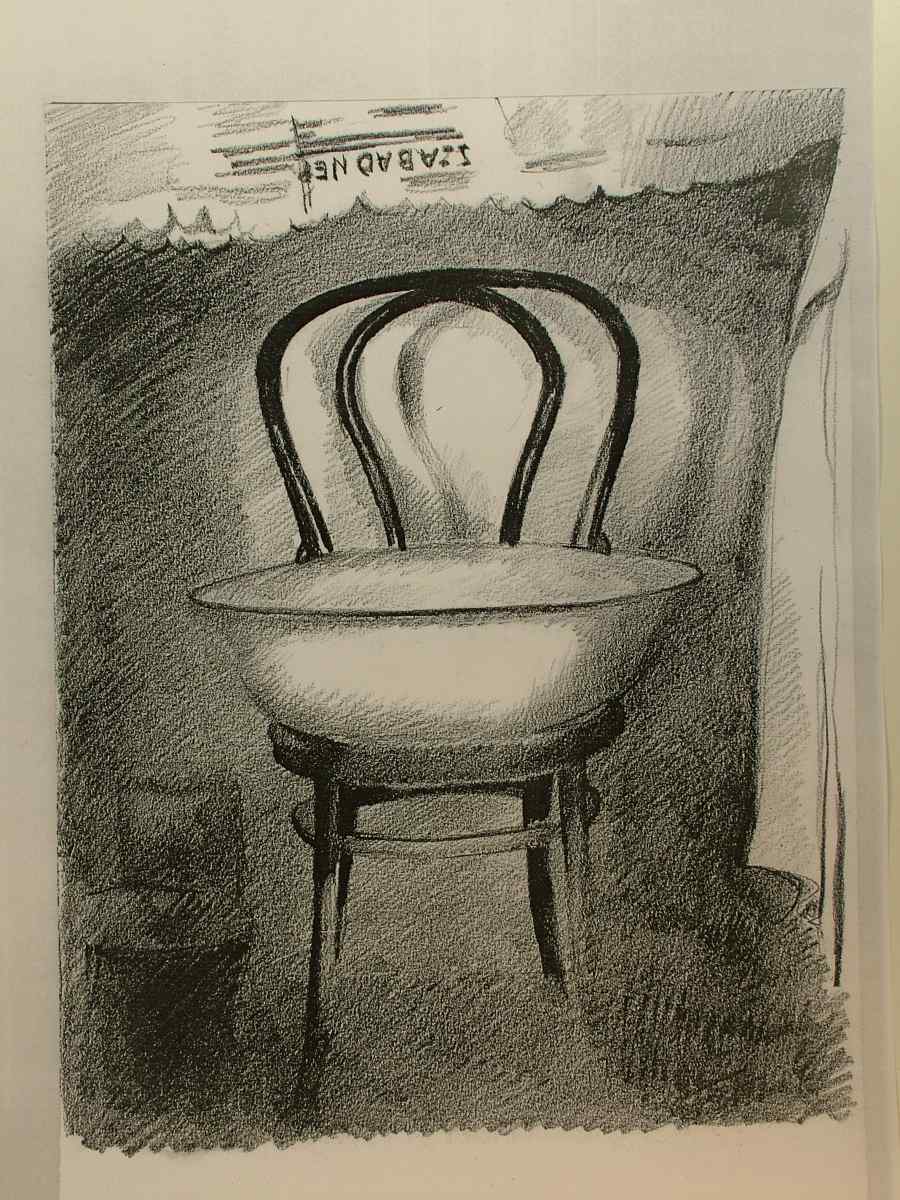

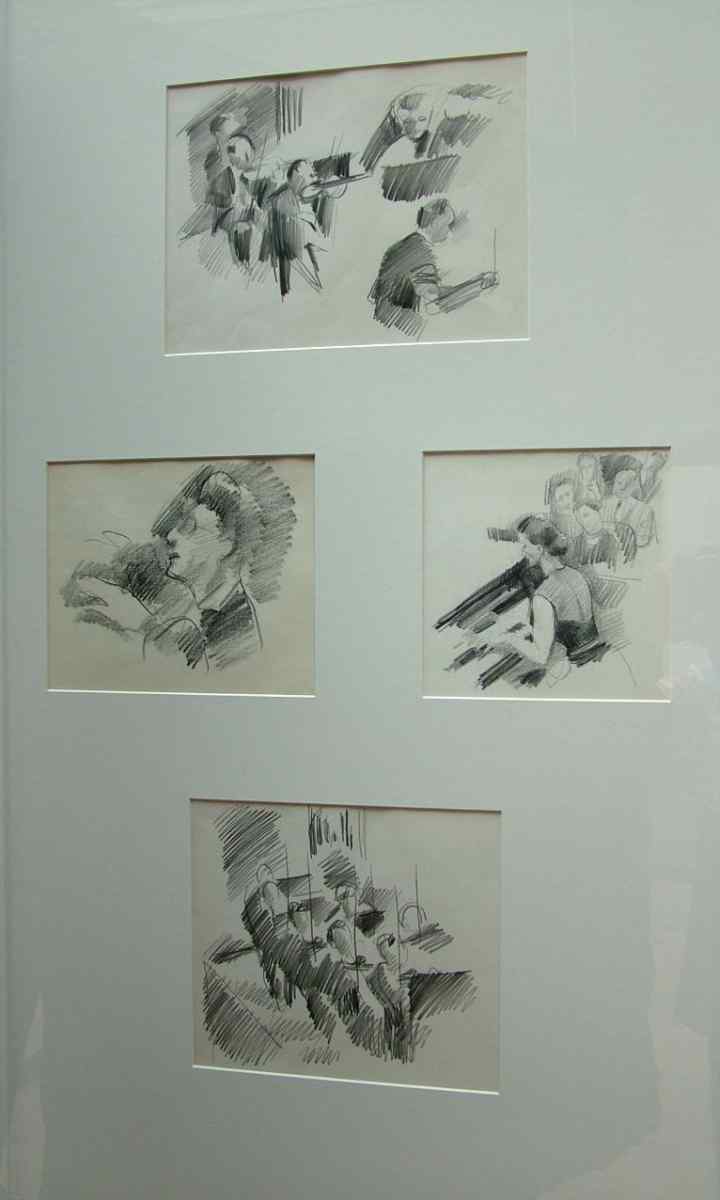

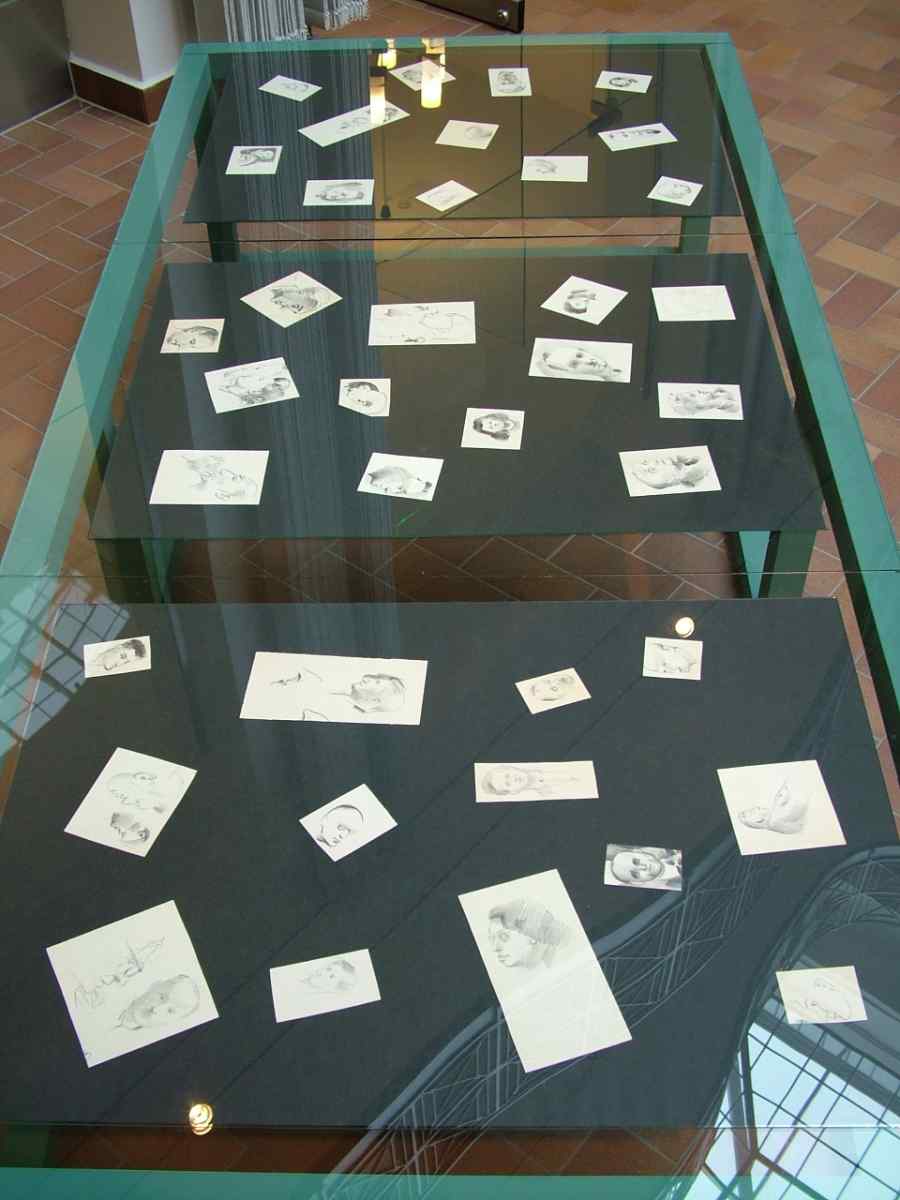

This year OSA Archives was granted the privilege of presenting in Budapest for the first time Endre Rozsda’s extraordinary set of drawings, an artistic diary portraying everyday life in Hungary throughout the 1950s. It was an obvious idea to combine the oral testimonies provided by Hungarian refugees with pictorial testimonies from the same epoch sketched by a world famous Hungarian émigré artist who had also left the country in 1956. The works of Rozsda are organized around certain topics such as the court room, the hospital, the coffee-house, the concert hall, the baths, literature, political meetings and sessions and the countryside. It was not a difficult task to select direct or indirect references to these topics from the interviews. We tried to sort out short excerpts from the oral testimonies of unknown Hungarian refugees who represented various segments of society, and from interviews conducted with well-known Hungarian public figures, intellectuals, artists like Zoltán Benko, former prisoner of the Recsk concentration camp, the poet György Faludy (recently deceased at the age of 96), who also had his term in Recsk, light music composer Imre Gordon and Tamás Aczél, the disillusioned Stalinist writer who became a prominent émigré chronicler of the revolution abroadand movie director Istán Erdélyi, who compiled the first documentary film on the revolution "Ungarn in Flammen" showed in the West. We hope that the interviews provide a vivid supplement to the world Rozsda depicted and that both the interviews and the drawings recall a world to which, fifty years ago, the 1956 Hungarian revolution dealt the first serious blow.