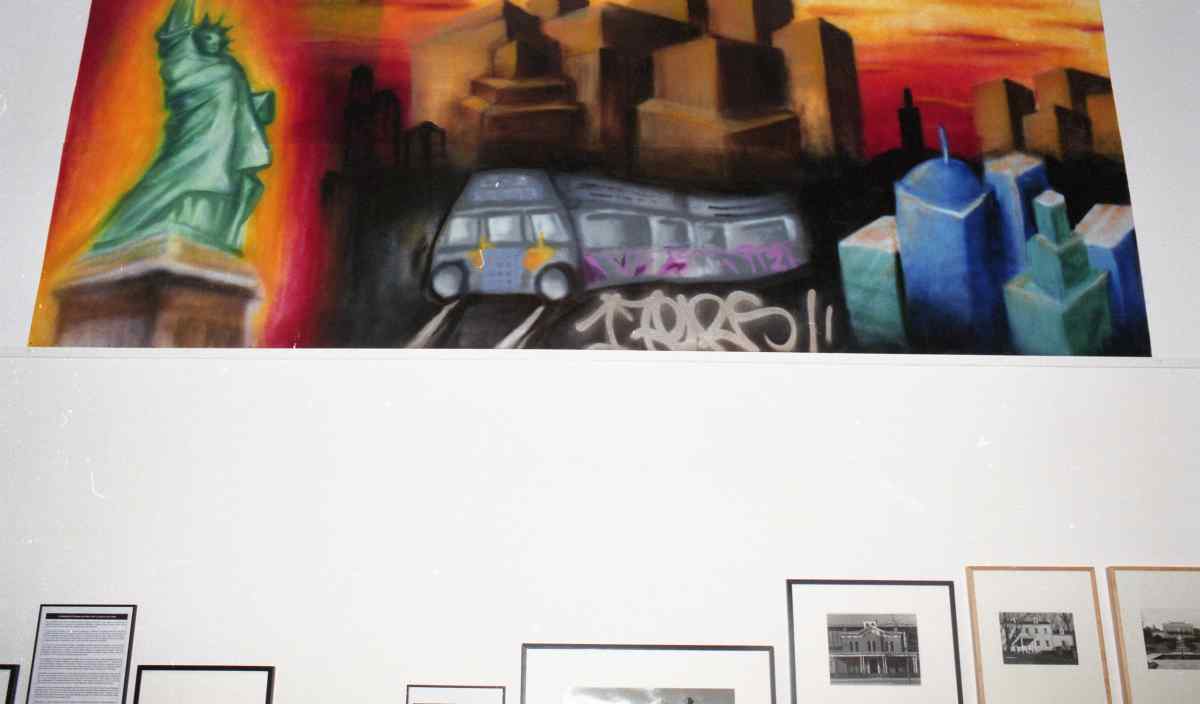

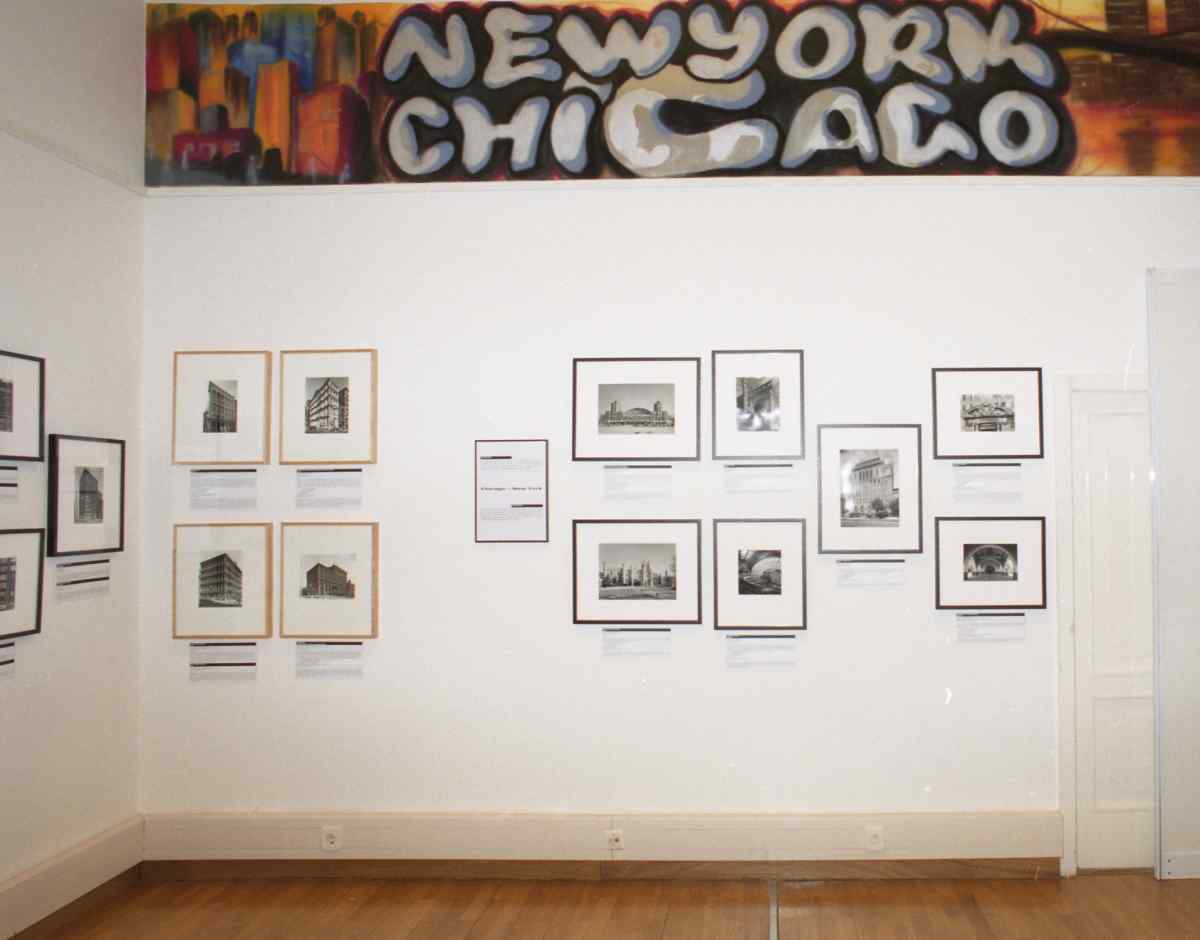

Landmarks of Chicago and New York

A Tale of Two Cities

Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs

Historic Landmarks Preservation Center, New York

U.S. Embassy in Budapest

This exhibition of more than 150 black-and-white photographs represents a cross section of the thousands of significant buildings that are protected by local landmark designation in Chicago and New York City. The story of how this came to pass is both as similar and as different as the cities themselves.

The preservation movement in both cities was, in large part, a response to demolition threats that occurred to significant structures during the building boom of the post-World War II years. For New Yorkers, the call to action as the 1963 demolition of Pennsylvania Station, a Beaux Arts masterpiece designed by McKim, Mead & White (1902–04). Two years later, New York City passed legislation that would help protect other significant structures from demolition or damaging alteration, establishing the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

One of the key events that inspired Chicago’s preservation movement was the near demolition in 1957 of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famed Robie House, located in Hyde Park on the city’s South Side. Another was the unsuccessful 1960 effort to save Adler & Sullivan’s Garrick Theater Building, an important early skyscraper. Even H.H. Richardson’s Glessner House on South Prairie Avenue seemed destined for demolition in the early 1960’s until it was purchased by a concerned group of architects and preservationists.

As a response to these growing preservation concerns, the City council of Chicago in 1968 established the present-day commission on Chicago Landmarks and empowered it to identify and protect the city’s historical and architectural heritage. Among the first buildings to be given protective landmark status were considered to be the precursors of modern architecture, such as the city’s pioneer skyscrapers (Carson Pirie Scott, Monadnock, Reliance and Rookery) and such milestones in residential design as the Charnley, Glessner, Madlener and Robie houses.

The number of protected landmarks in the two cities varies widely, as benefitting the differences in their size and age. New York has designated more than 1,000 individual landmarks and 73 districts, including several buildings from the 17th and 18th centuries, such as the Conference House (1675) and Gracie Mansion (1799). Chicago, on the other hand, has designated 145 individual landmarks and 31 districts—only a handful prior to the fire of 1871, such as the Noble House (1833), Clarke House (1836), the I & M Canal Origins Site (1836) and the Wingert House (1854).

Today the two cities are paying increasing attention to landmarks from the recent past. Among the newly designated landmarks in New York City are the Levet House (1952), the Seagram Building (1958), the Unisphere from the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the TWA Terminal (1962) and the Ford Foundation Building (1967). Chicago’s recent designations have included the Bachman House (1948), 860-880 Lake Shore Drive (1949), Crown Hall (1956), Inland Steel (1957) and the Chess Records Studios (1957).

Photography is a critical component of each city’s approach to generating public support for landmark designation. New York City’s images are the work of young photographers who were commissioned for the book Landmarks of New York III by Barbaralee Diamonstein. Chicago’s landmarks were photographed by some the city’s most notable photographers, commissioned at the time of the proposed designation.

Landmarks of Chicago and New York: A Tale of Two Cities has been organized in Chicago by the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, in cooperation with the Commission on Chicago Landmarks and the Historic Landmarks Preservation Center, New York. Kenneth C. Burkhart served as exhibition coordinator.