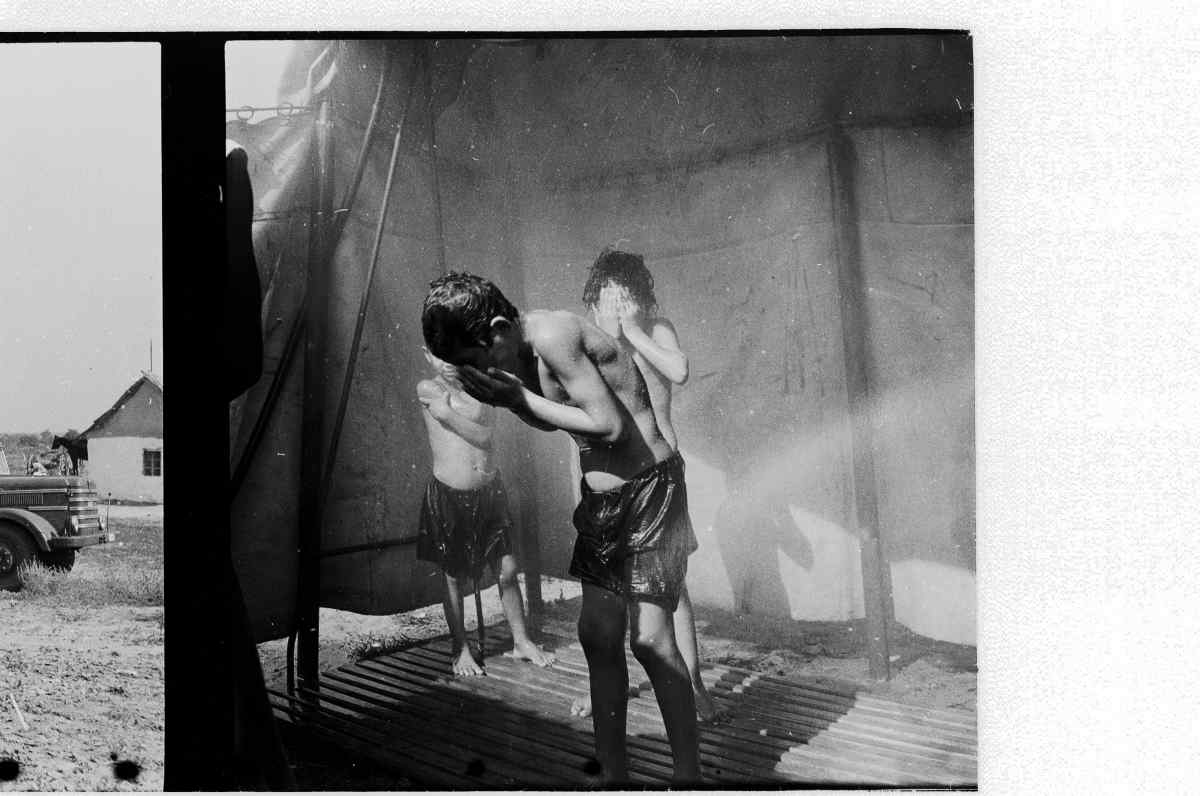

Forced Bathing in Hungary

Shaving, Stripping, Public Humiliation: Disinfecting Gypsy Settlements during Socialism

Roma Sajtóközpont / Roma Press Center

Healthcare campaigns aimed at “cleaning up” Gypsy settlements began at the end of World War II and continued to persist until the political transition in 1989. This included “cleaning” techniques such as close cropping and mass baths in caustic chemicals (among them DDT, internationally banned in 1968 for its poisonous carcinogenic contents). Although, according to documentation, lack of sewage, water conduits, and unsanitary toilet conditions were widespread throughout society during the fifties, the state only punished the Romani community for its poor health conditions. The punishment forced disinfections of entire communities in the form of shavings and bathings, that normally took place at dawn.

Forced bathing affected more than half of the Romani community of Hungary, according to the documents available. In some places, it even affected those Roma who had previously moved out of the colonies and some Hungarians living with the Roma as well.

The bathings were also accompanied by police brutality. Very often, even those who had no sign of lice had their head shaved as well as those who did: all of them were then conducted through the village in a “shame procession” or gathered in tents to be submitted to a “chemical shower”. The authorities proved to be quite unsympathetic toward the humiliated Roma. It was years into the campaign when a 1961 resolution finally announced: “Only women can assist in bathing Romani women” and, in the same year, the authorities decided that “only those Gypsies should be checked, bathed and disinfected, who had previously been infected with lice”. (Further reports indicate that this resolution was often ignored by local councils.)

The government had been promising the elimination of Roma colonies since the beginning of the fifties. However, through time, these efforts failed to gain ground, and local councils in many areas even began establishing new colonies. By 1971, two-thirds of Romani families continued to live in these colonies, mostly without sewage, running water, and electricity. However, the government continued to persist in this type of campaign, and in the early 1980s, huge sums were spent on mass bathing actions in the colonies—colonies where, 25 years after the first respective resolution had been issued, no water conduit had been installed and there had been no effort made to improve sanitation facilities. In many areas, the living conditions remain identical today.

The Open Society Archive presented the documentation of these bathings in its exhibition, and the Roma Press Center has published a compilation of memories and other documents (Forced bathings in Hungary 1940-85. Roma Press Center Books, 3).