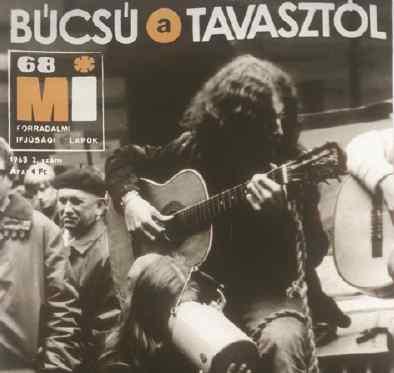

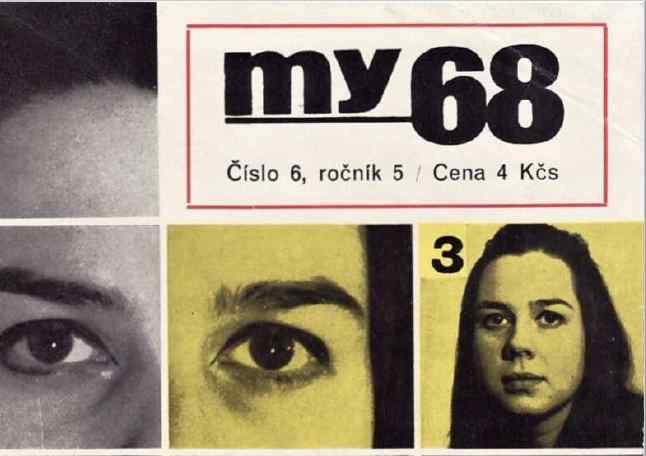

Farewell to Spring

Revolutionary Youth Magazines 1968. Nr. 2

ALTORJAY Gábor, Jerzy BEREŚ, Eugen BRIKCIUS, Stano FILKO, Tomislav GOTOVAC, GULYÁS Gyula, Matjaž HANŽEK, Tadeusz KANTOR, KEMÉNY György, Milan KNÍŽÁK, KONKOLY Gyula, Július KOLLER, Marko POGAČNIK, Red Peristyle, SZENTJÓBY Tamás, Želimir ŽILNIK, et.al.

kiállítás- és grafikai design / exhibition and graphic design by KRISTÓF Krisztián

MKE - Kortárs művészetelméleti és kurátori ismeretek, MA / Art Theory and Curatorial Studies Programs, MA

The year of 1968 started with great hopes in some Central- and Eastern European countries: for a brief moment it seemed that strict ideology was being replaced by political pragmatism. Elements of consumer culture, and even the private sector, appeared; cultural censorship was loosened – or even lifted. The whirlwind of the Western protest movements reached the region as well, while counter culture also left its mark on Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, and Hungary. And similarly to Western youth, young people from behind the Iron Curtain also wanted to correct the mistakes of the previous generation, and found their own voice and their own ways to express themselves. Creating a fictional international youth magazine, the exhibition “Farewell to Spring” presents this thriving and hopeful period of student protests, happenings and other events of youth- and counter culture, which ended with the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.

***

In June 1968, a circle of artists around the Foksal Gallery organized a party in the suburbs of Warsaw, known as the “Zalesie Ball”. The event, also entitled “Farewell to Spring”, with all its grotesque and whimsical features, was, according to one of the participants, the only adequate response to the atmosphere of hopelessness and defeat that was so pervasive in the period after the events of the “Polish March”. Around the same time, on the evening of June 4, 1968 actor Stevo Žigon delivered Robespierre’s speech from Georg Büchner’s 1835 play, Danton’s Death to a crowd of anxious students gathered in the inner yard of the School of Philosophy in Belgrade. His speech, as we see in the film “June Turmoil” by Želimir Žilnik, drove the crowd into a frenzy.

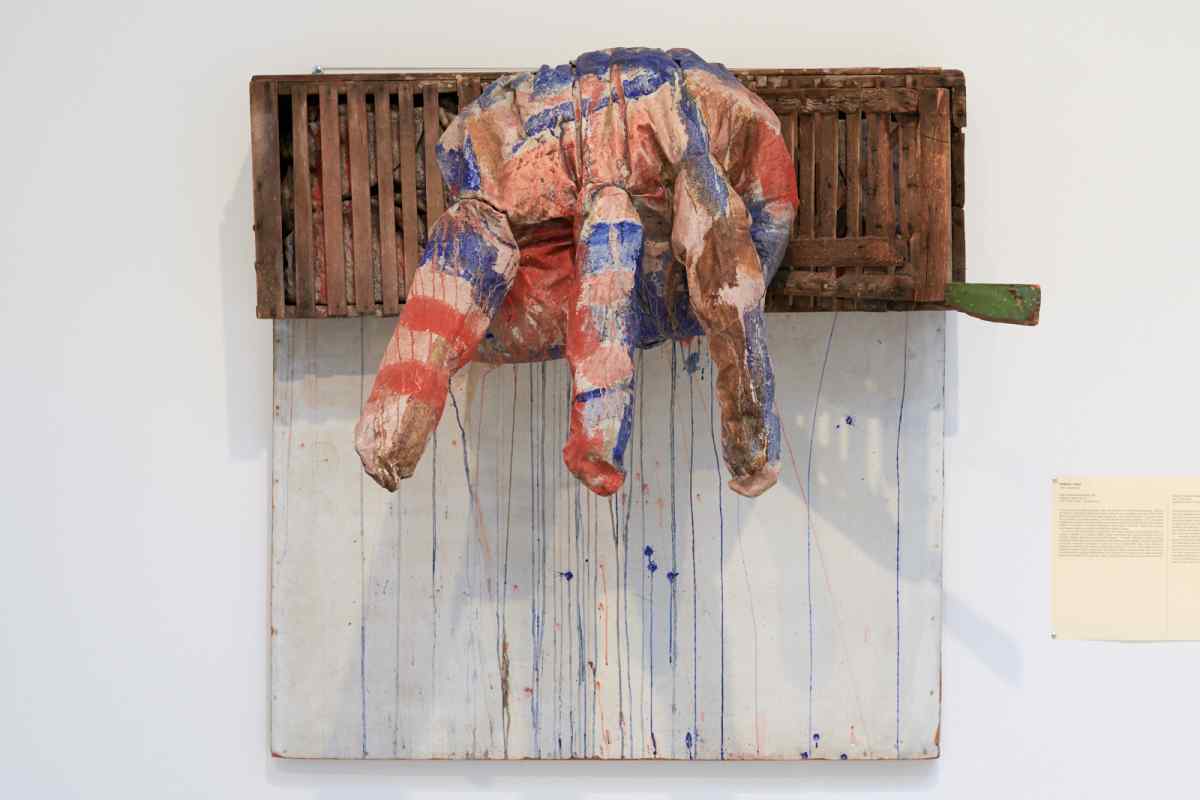

Symbolic actions – performative actions in everyday life, as well as artistic performances – have the potential to create or undermine social reality. In the 1960s, this insight quickly spread among scientists and theorists all over the world and it, too, led to a large number of direct actions—“go-ins”, “sit-ins”, and “sleep-ins”—during the different student protests, as well as to the discovery of performativity in visual arts through happenings and other manifestations. In fact, artistic performances often foreshadowed, accompanied or commented on political demonstrations that, for their part, also drew upon performative techniques.

The spirit of 1968 reached the different Eastern and Central European countries at a different pace: in the summer of 1968, while Polish intellectuals had to cope with the general sense of despair and defeat after the events of the “Polish March,”, students in Yugoslavia began to protest against the “Red Bourgeoisie” and for a more just, equal and democratic society. In Hungary, the political leadership went to great lengths to avoid allowing similar protests to evolve: drawing on the experience of the 1956 revolution, they did everything they could to pacify and domesticate the youth and to (further) marginalize counter-culture. With the introduction of the New Economic Mechanism, and with more open cultural policies, protest movements and subversive artistic actions were indeed confined to closed circles. Meanwhile, in Czechoslovakia, young people—along with the leaders of their country—believed that the period of “Socialism with a human face” had really begun and enjoyed the newly earned—and short-lived—freedom of the summer of 1968: for instance, with so-called máničky (long-haired young people) appropriating the public space for happenings and impromptu beat-concerts and a flourishing cultural scene made possible by the lifting of censorship.

It was not only the dreams of Czechoslovakian youth that were crushed by the tanks of the Warsaw Pact countries: political protest was met with often violent repression by state agencies all over the Eastern Block, and culture came, again, under even stricter supervision by the authorities. Still, the genie was already out of the bottle. The events of 1968 proved in the Eastern Block too that there was a new generation that did not necessarily accept the existing rules and was ready to protest against them; and that symbolic actions can indeed create or undermine social reality.