East is Red

Posters, objects and photos from the period of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976)

BARACS Dénes

design: NEMZETES Ferenc

A Westminster Egyetem Demokráciakutató Központja / Centre for the Study of Democracy of the Westminster University

At the time of their creation these materials were under stricter prohibition than in the decadent Western culture. While the names Antonioni, the Beatles or Sartre were tolerated in Budapest, Mao Zetong, Jiang Qing or Lin Biao were only pronounced with obligatory disapproval by those loyal to the regimes of Central and Eastern Europe. Yet, were it not for Mao, the still worshiped '68 would not have taken place and the Hungarian democratic opposition would never have emerged. For the silence around what was believed to be true socialism made many realize, for the first time, that the socialism of the 1960s was not the real one.

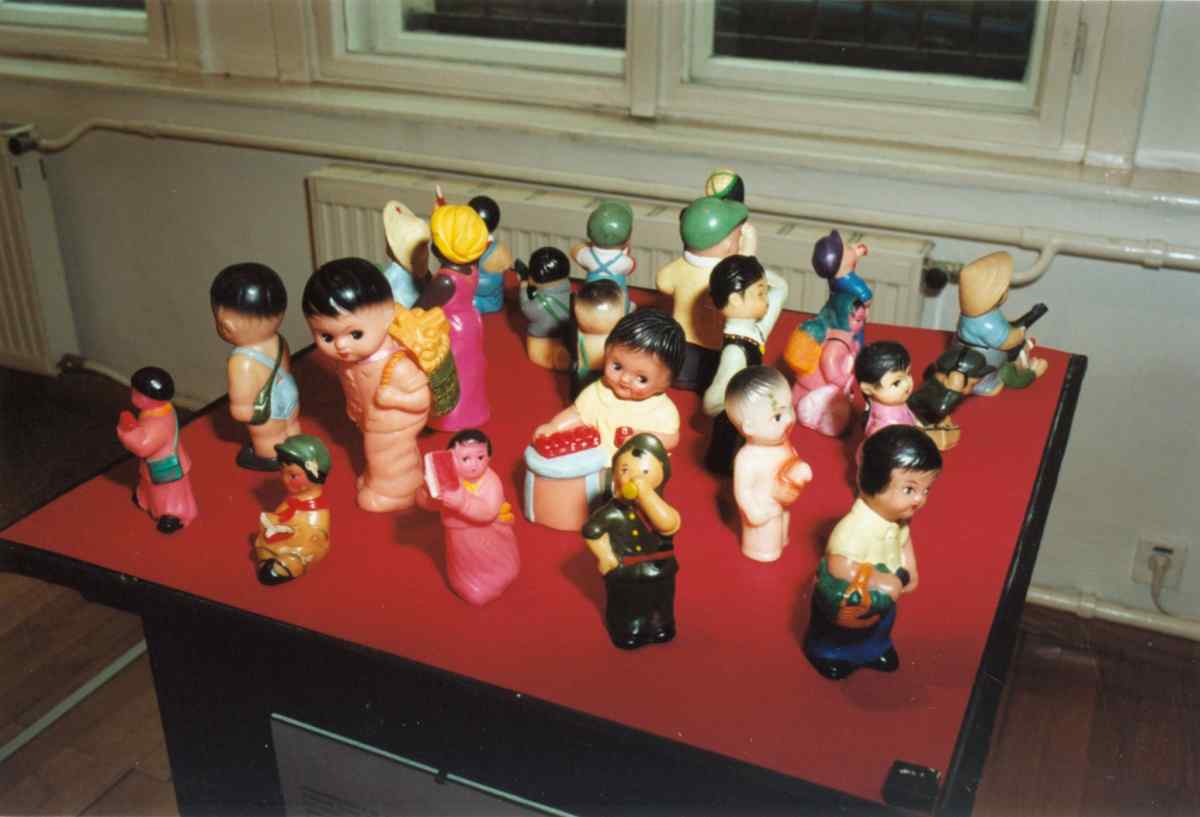

What can visitors expect to see? They can see the Red Book, and the ideological rubber doll. They can imagine how Chinese toddlers sitting on the pot studied the teaching of the Great Helmsman just to get up and play anti-imperialists and critics of deviationists, and prepare with toy guns for the fight that would leave socialism the single ideology on Earth. They can also expect to see a great many posters calling the people of the Divine Empire to build socialism, to annihilate the enemy, to increase production and follow Dazhai's and Daqing's example, as taught by Mao. The posters were also designed to convince the people that outside of China the teaching of the Chairman was studied and followed in several Asian, African and Latin American countries. And the Chairman was ubiquitous. Like a red-hot Sun he lit up the hearts of his subjects who had to content themselves with the light of 25-watt bulbs if they wanted illumination other than ideological.

Misery, chaos, mass terror and national repression. These were the pictures that circulated in the press of the socialist world of that period. China was severely criticized by the Soviet Union for its nationality policy and occasionally it appeared to be the safe harbor for Uigurs and Kazakhs fleeing from Xinjiang. True, many of the refugees soon found themselves in prison camps as violators of frontiers, rather than in a safe haven.

Nevertheless, it would not be fair to show only the chaos and mass hysteria. No political propagandist, however ingenious, is able to make nearly one billion people believe a lie for a decade. The enthusiasm must have had some basis even if now, sobering, it is the Chinese who feel particularly ashamed and refuse to remember how it all happened.

In order to clarify this effect not only the tools used by the official China to make fanatics of its subjects are displayed, but also the impact of this process on Hungary. The curiosity of the exhibition is that it addresses the impact of Maoism on Eastern and Central Europe, something never before presented to the Hungarian public. And finally, having gone through the exhibition, visitors will see a photo collection on show for the first time. Dénes Baracs, a former correspondent of the Hungarian News Agency in Beijing, has published three books on China of the 1970s and 80s. Photos of his own life, however, are first exhibited in public here. An Eastern-Central European citizen in Beijing. It must have been an extraordinary life. Let’s have a look at it!