Bodies in Formation

The History of the Spartakiads

design: TAMÁSI Miklós

Tyrs Nemzeti Testnevelési és Sportmúzeum, Prága / Tyrs Musuem of Physical Education and Sport, Prague

Testnevélési és Sportmúzeum / Musuem of Physical Education and Sports, Budapest

Magyar Pedagógiai Múzeum / Hungarian Museum of Pedagogy, Budapest

Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum – Történeti Fényképtár / Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Collection, Budapest

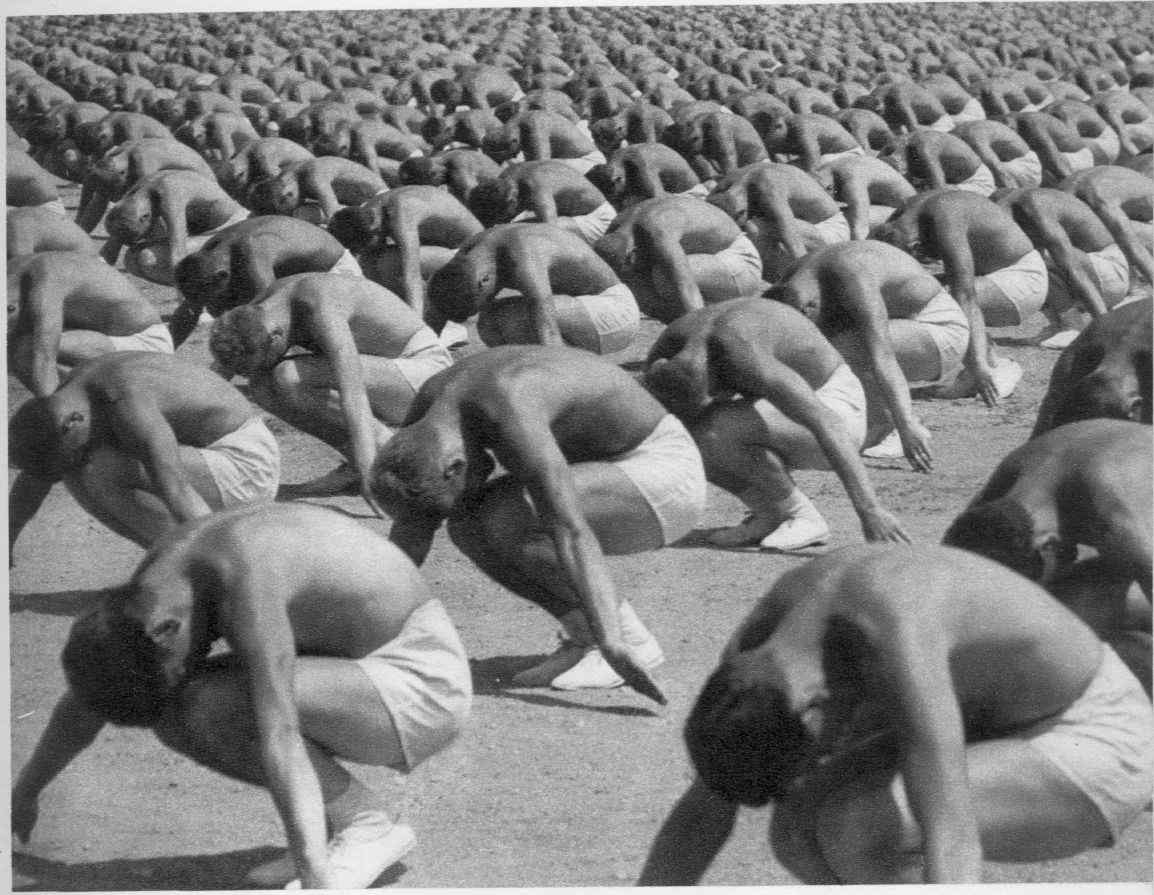

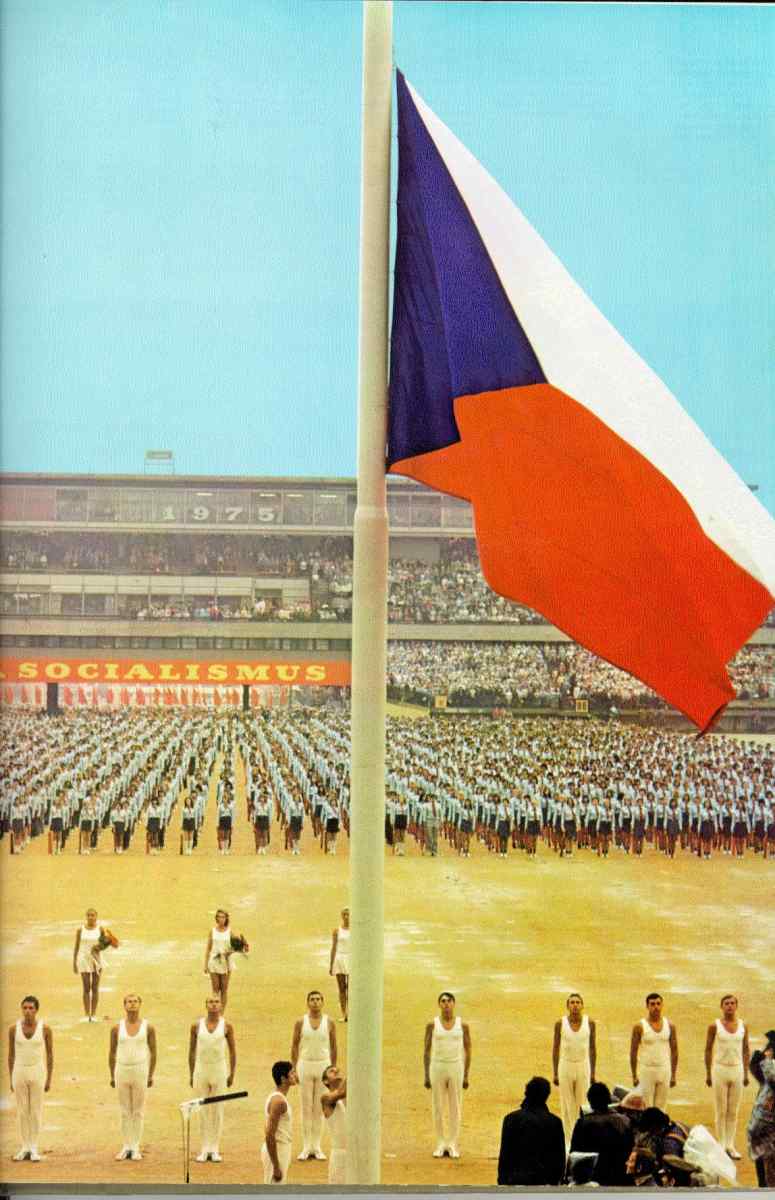

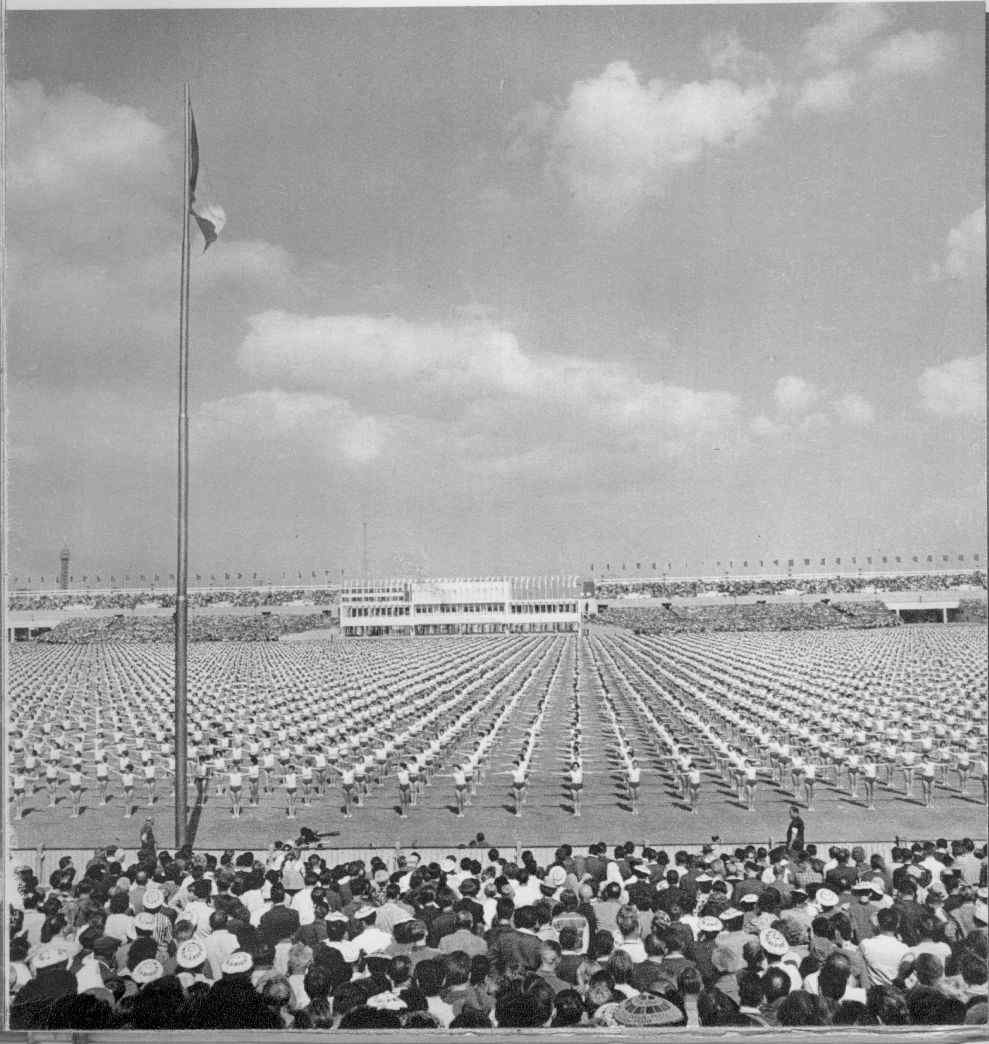

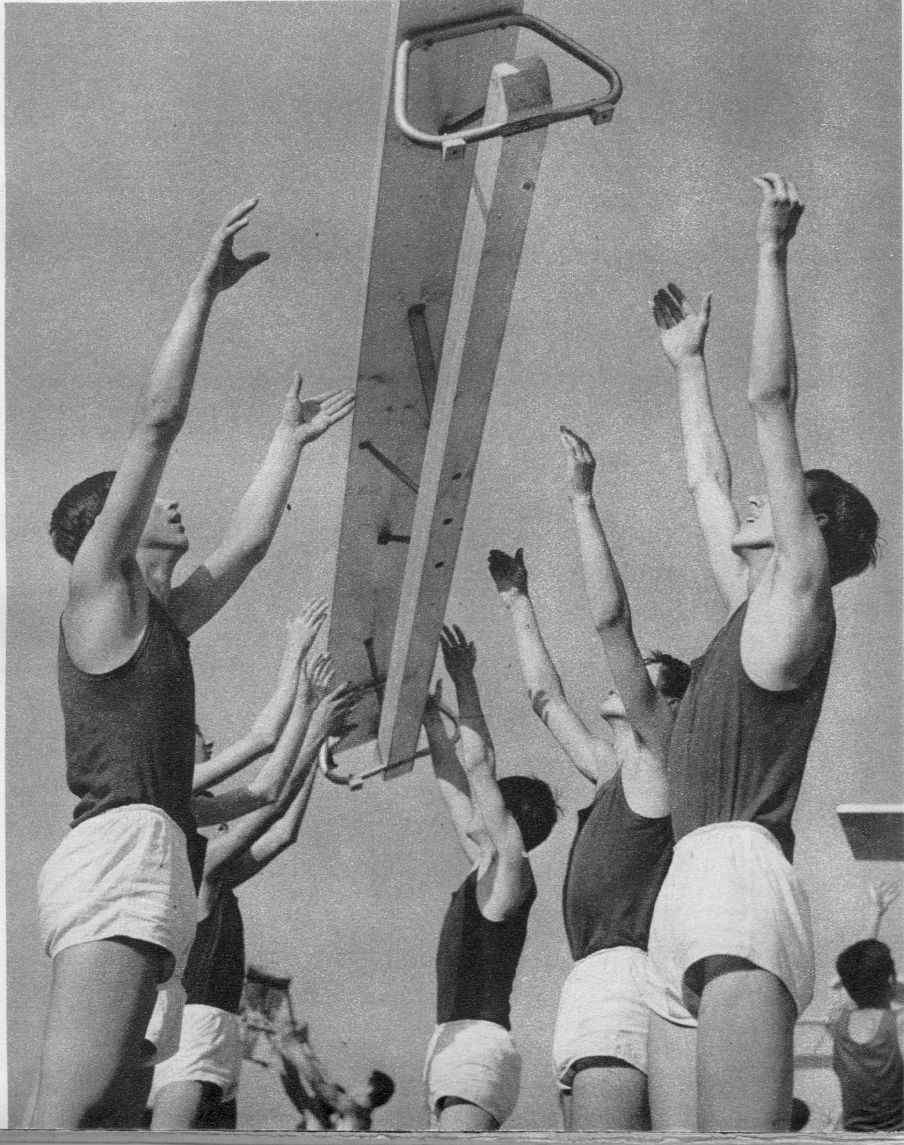

Salvo. With a deafening roar fourteen thousand soldiers ran through the gates of Prague’s Strahov Stadium, the biggest stadium in the world, covering an area larger than eight football pitches. They launched into a performance that drew gasps of admiration—and sometimes fright—from the crowd. The musical accompaniment built up to a crescendo as a huge five-cornered star formed from their bodies with the corners spreading from the stands on one side to those on the other. In the middle of the star, a soldier climbed the pyramid of human bodies. He spread his arms wide, raised his eyes to the sky, and from the Strahov Stadium, the “hymn of the working people”—the Internationale—sounded over Prague.

Performances such as these were typical of the Czechoslovak Spartakiads. They were some of the most spectacular mass gymnastic displays ever held, as the ritual of synchronized mass movements played an important role in all communist countries. The Turn- und Sportfests in GDR, mass gymnastics displays in front of the tribune of the Politburo during the May Day parades in Red Square in the Soviet Union or at Felvonulási Square in Hungary were all a variation on the same theme.

More than a hundred photographs, including those taken by such names as Alexander Rodchenko, Sandor Bojár or World Press Photo winner Zdenek Lhoták, accompanied by secret archival material, showed both the striking mass gymnastic performances themselves and the techniques of manipulation and choreography behind them. As mass gymnastics was not a communist invention, rare archival footage never shown before, such as a gymnastic display in front of the Czar and his family in 1913, will be shown to demonstrate the roots of this extraordinary phenomenon. Next to the original posters and propaganda materials, the visitor had the opportunity to see exercise tools and equipment, such as the wooden hammers used by communist gymnasts at the first Prague Spartakiad in 1921 to express “the determination of revolutionary workers to fight under the leadership of the party to overthrow capitalist supremacy.” Finally, standing on the special grid covering the floor of the Galeria Centralis, the visitor is given a chance to experience personally the dehumanizing effect of mass gymnastic performances, when a human being was reduced to the abstract intersection of x and y axes.

With the help of explanatory texts and the exhibition catalog, the visitor could see behind the attractive visual material. The exhibition touched on several important theoretical issues, starting with Foucault’s disciplinary society, followed by semiotic ritual analysis, and the question of legitimization and visual representation. Most importantly, it analyzed the relationship between mass bodies and power. The body alone is the most powerful metaphor for life and its meaning; multiplied bodies in mass gymnastic displays are in the same way a metaphor for the ideal society and its leadership. The communist regimes could not miss the opportunity to use the enormous symbolic potential of mass gymnastic performances. They transformed the key concepts that the performances proffered—strength, youth, beauty, and discipline—into symbols of a strong, young, beautiful, and disciplined socialist society. The coordinated movements of the gymnasts served as a final proof of “the readiness of the people to fulfill the wise and courageous plans of the leadership”.