Atom

On the 20th Anniversary of the Chernobyl Catastrophe

design: TAMÁSI Miklós

Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University

Department of History, Central European University

Center for History of Physics

The American Institute of Physics

National Security Archives, USA

International Atomic Energy Agency, Austria

Polytechnical Museum (Mozskva / Moscow)

Obninsk Institute of Physics and Power Engineering, Oroszország / Russia (z első atomerőmű telepe, ma múzeum / home of the first nuclear power plant, now a museum)

Nuclear Physiscs Institute, Csehország / Czech Republic

Joint Institute of Nuclear Research, Dubna, Oroszország / Russia

Paksi Atomerőmű Rt., Tájékoztató és Látogató Központ

MTA debreceni Atommagkutató Intézet

Magyar Polgári Védelmi Szövetség Országos Elnökség

János Kórház budai sziklakórháza

Műszaki Múzeum

Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára

The occasion for this exhibition is the 20th anniversary of the Chernobyl catastrophe. The exhibition focuses retrospectively on the history of nuclear research and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, primarily in the USSR and other former Communist countries. This topic was one of the most crucial, and painfully sensitive, issues of the past century and the Cold War period.

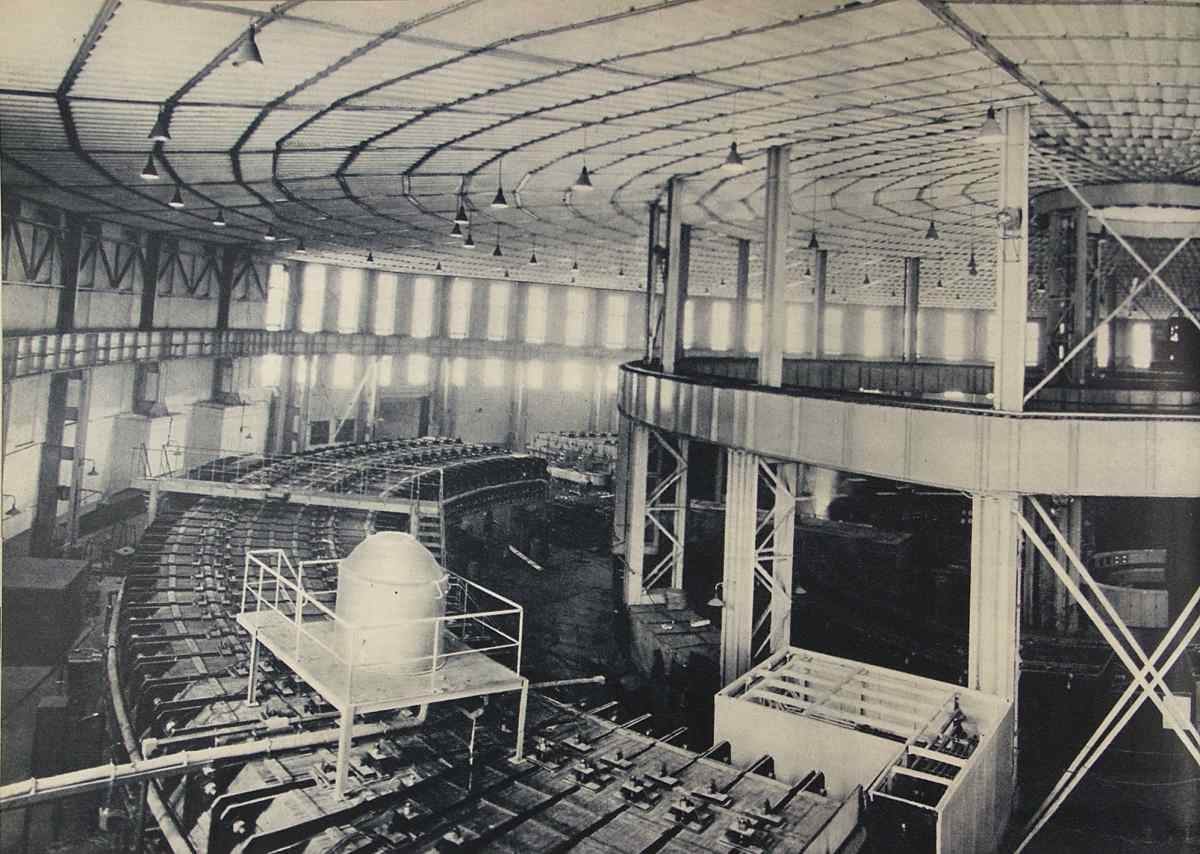

It was not our intention to provide a detailed historical exposé. Instead, the curators of the exhibition wish to give an overall picture of the fascination and the fear—both of them very real at the time—that were generated by the atom. The exhibition displays models, objects, posters, original documents, contemporary works of art, and audiovisual artifacts.

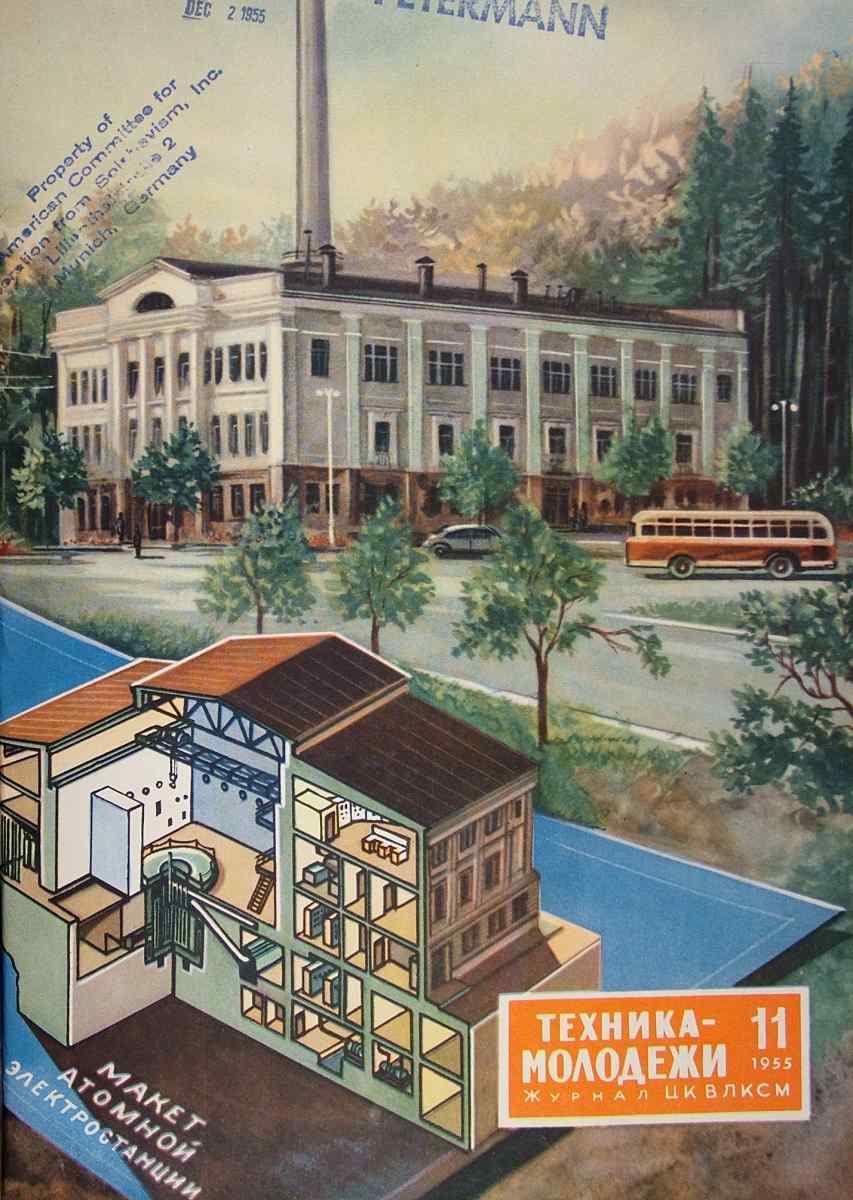

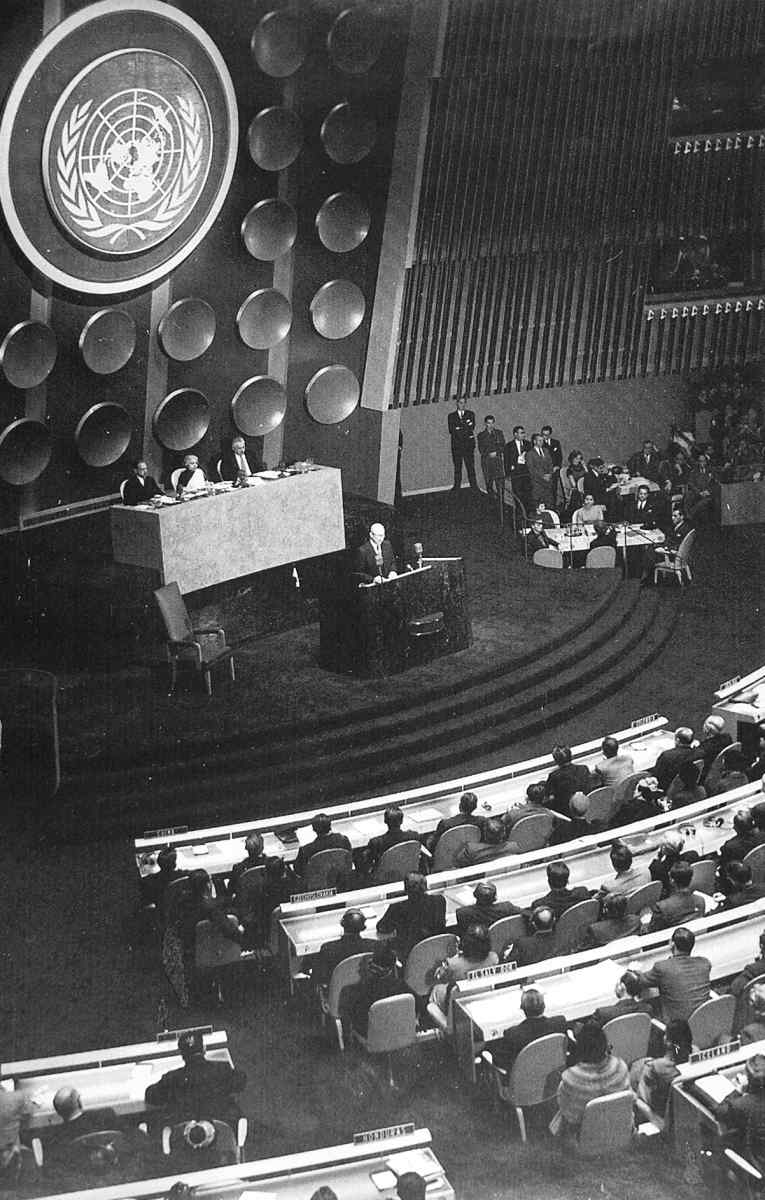

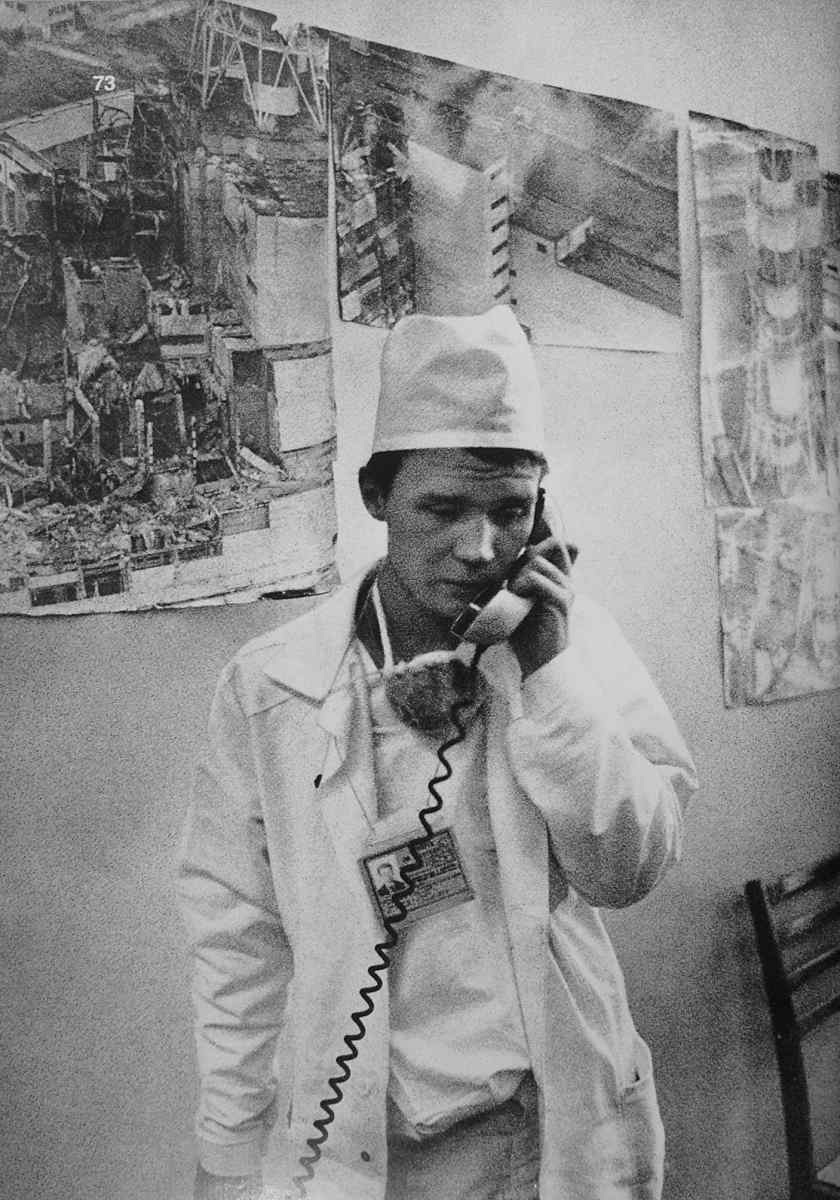

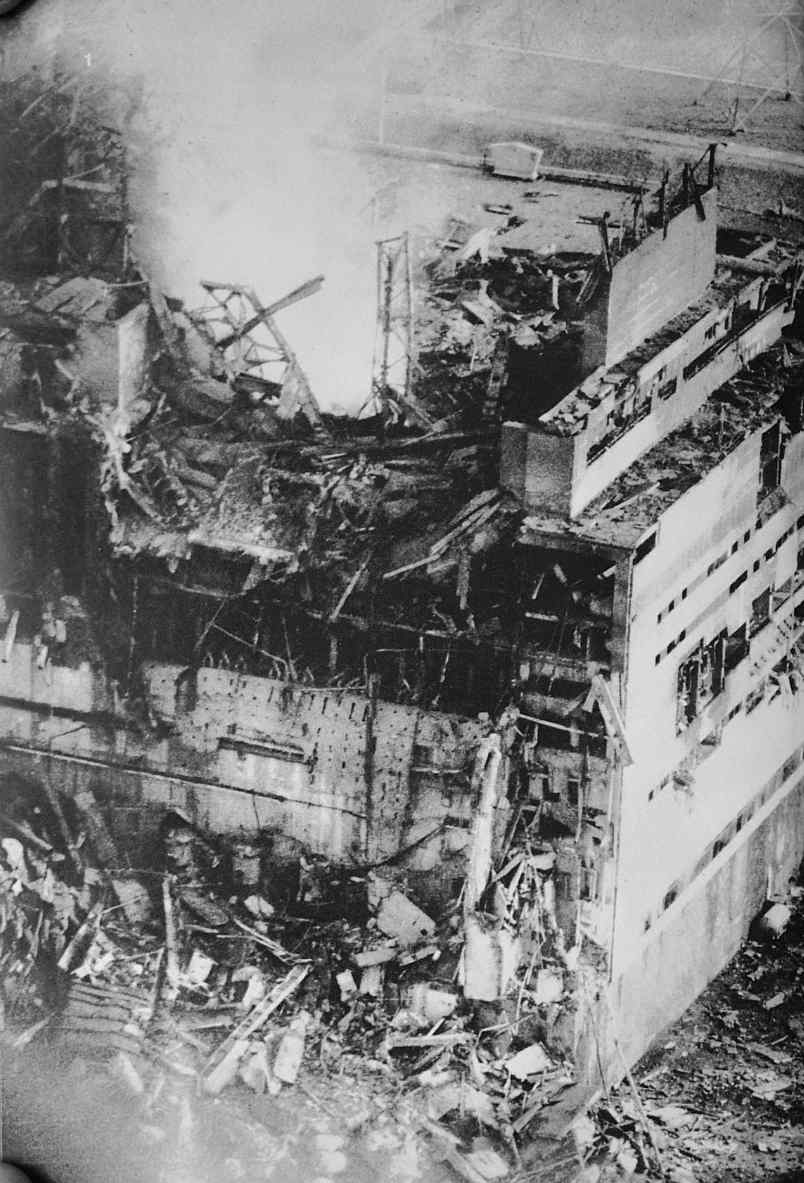

In 1953 US President Eisenhower announced his politically naive (or perhaps intentionally faux-naive) global program for the peaceful use of nuclear energy. In the early 1960s, a new slogan was adopted in the USSR: “Nuclear energy for every household”. This slogan truly reflects the prevailing euphoria and the commitment of both the political leadership and the general public to this apparently unlimited technological development. Nuclear energy gave light and heat, cured, took man into space, and smashed the thick ice of the frozen North. At the same time, the mysterious atom was a source of more or less well-founded fears: its murderous rays invisibly penetrated our homes, it poisons our land and water, “nuclear winter” threatened global catastrophe, atomic explosions killed hundreds of thousands of people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and radiation wiped out every member of the first rescue team that arrived in Chernobyl.

The atom was at one and the same time the symbol of utopia and of endless abundance, and a modern vision of the apocalypse. During the Cold War, the atom was an instrument of mutual blackmail between the two world orders. An invisible Cold War was fought to spy out each other’s secrets. The tight web of secrecy which surrounded the atom kept the fantasy, the awe, the suspicion and the mutual distrust alive. The history of the nuclear programs of the former Soviet block has not yet been written. It was only in 1991 that Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Federation, authorized access to certain files in the secret archives which documented the Soviet nuclear program. Over the last decade all the nuclear apparatus of the previous period has been put on display in museums and now some of the industrial buildings themselves have been turned into tourist attractions.

The exhibition aims to present the mutual visions and fears related to the atom in the context of the Cold War. The borderline between the peaceful and military uses of nuclear research was never very clear, and the curators want to make us aware of this gray zone. The exploitation of raw materials in East Europe were presented in a separate section, combined with the economic and political aspects of uranium mining and with the joint nuclear research program of the former Communist countries. The exhibition also focuses on the Chernobyl catastrophe: the process which led to the catastrophe, the catastrophe itself and its environmental and political consequences.

The exhibition presents the particular role played by civil defense organizations and civil emergency plans (mobilization, ideological indoctrination, military morale and tools for maintaining hysteria) in the Communist regimes. The curators show the correlation between the nuclear heritage and the collapse of Communism, and the ambiguous role of nuclear power for several of the post-Soviet nations struggling to achieve energy self-sufficiency.

Today the protean and invisible atom has become visible through our everyday predicament. The current problems and difficulties of international cooperation, and conventions about the control of the use of nuclear weapons or the safe operation of nuclear plants have often lagged behind immediate political realities. Nuclear power and its future use are still very sensitive and delicate issues both in the West and in the former Communist countries. Serious debates continue about the safe operation of nuclear plants and about how to prevent terrorist organizations from acquiring nuclear weapons. The problem of nuclear waste disposal remains unsolved. Fear and euphoria, war and peace, utopia and reality—these issues remain to be settled. The nuclear clock is still ticking, in the famous image of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, and we still wonder how closely it approaches the hour of midnight.